Truck Parking Crisis Gets Renewed Legislator Attention Amid Supply Chain Woes

By now, every working professional is well aware of the significance of a stable, resilient and dynamic supply chain. COVID, geopolitical crises and freak accidents made sure of that. Most of the acute supply chain disruptions felt in the US happened to the chain on an international level rather than a domestic one. While of course the US’ local economies and local flow of goods continue to feel pressure from the pandemic’s market-crunching effects, strategic attention from legislators and market leaders has centered on maneuvering the receiving end of global trade dynamics. This includes everything from persisting conflict in Eurasia, to new sanctions and tariffs, to shipping slowdowns.

However, a glaring domestic challenge for the US supply chain is just as important to strategically maneuver and solve, as it’s only growing in costs and negative externalities. As the US amps up its infrastructure spending, and with supply chain resiliency front of mind, attention shifts back to an often-overlooked issue in the nation: the lack of availability and the lack of direct funding for freight truck parking.

In 2020, trucking accounted for the transportation of 72.5% of US freight, or 10.23 billion tons, according to the ATA. Clearly, trucking continues to be a critical part of the US’ flow of goods; trucking as a mode of logistics transport is often referred to as a “barometer of the US economy.” Despite this outsized role in our supply chain, truck drivers everywhere have struggled for years to find en route parking that does not decrease the efficiency of their deliveries or put their own safety at risk.

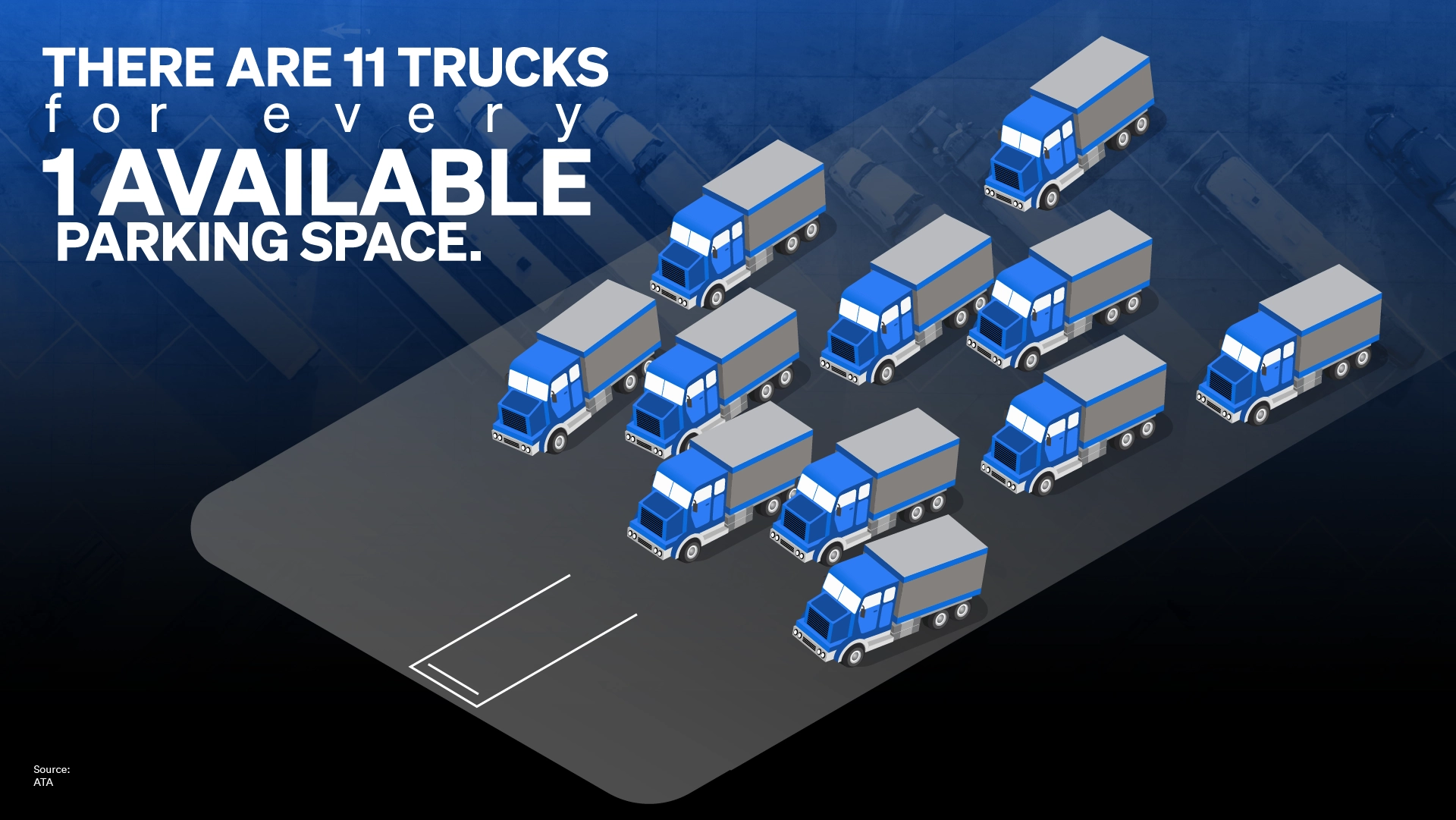

The FHA’s 2020 Jason’s Law Report, which we break down in more detail below, found that 98% of drivers have difficulties finding adequate parking throughout the nation. According to ATA reports, for every one available parking space, there are 11 drivers competing for the same space; the average driver spends 56 minutes a day simply searching for a place to park, which amounts to a 12% annual pay cut. To avoid a route change, late delivery, or trouble with their employer for not resting when they are supposed to, 58% of drivers stated they will park illegally at a minimum of three times a week. Many drivers end up with the lose-lose choice to illegally park or to risk driving over their limit; either option puts both the safety of the driver and others on the road at risk.

While on the road, truck drivers face long hours and strictly planned delivery routes, both of which motivate the need for quality parking infrastructure. According to tractor trailer training company CDS, OTR truck drivers average 300 days on the road a year with an average of 125,000 miles traveled in that time. Law requires drivers to take 34-hour rest periods for every 70+ hours of driving after an 8-day period of travel. Shorter-term requirements force property-carrying drivers to drive no more than 11 hours in a 14 consecutive-hour period, followed by 10 hours “off duty.” It can be extrapolated out from there how even just an hour of time per day devoted to searching for parking can incur enormous time, wage and sanity costs on drivers. With parking being limited, drivers often need to travel a further distance, maybe even off route, to find parking that is available and safe..

“In regions that don’t have adequate parking, there is a bit of a truck parking tax, if you will, in that it costs more to provide services to these regions. Because of the truck parking problem, drivers have to drive around, find other parking, maybe they have to pay more for parking in some places,” said Dr. Nicole Katsikides, Research Scientist at the Texas A&M Transportation Institute.

The Owner-Operator Independent Drivers Association vocalized the current state of frustration and inaction around truck parking during a recent roundtable hosted by the Federal Highway Administration. There, OOIDA Executive Vice President Lewie Pugh was blunt with the harsh reality he’s faced as an industry leader. Since he came aboard the OOIDA in 2004, there’s been plenty of conversation around solving a lack of truck parking via constructive roundtables, new technology investments, safety strategies for drivers, and limited federal funding programs. Even with this acknowledgement of the issue, little has been done to invest in parking infrastructure at scale.

“No matter how well a trucker plans, he can’t park if the spaces aren’t available,” Pugh said, as reported by Land Line.

If the US is to solve its supply chain problems, experts from each corner of the trucking industry believe funding for truck parking needs to be a major priority. US ecommerce growth shows no signs of slowing, with some studies pointing to ecommerce being the largest driver of US retail growth to the point where it’ll make up nearly 31% of total retail sales by 2026. Naturally, fulfilling that demand of goods will come with trucking needs and a supply chain cost.

Our manufacturing footprint is also set to place pressure on the supply chain. The ‘US-made’ materials, parts and services used for domestic production and completion of public projects, also known as the country’s domestic content percentage threshold, are going to be in high demand, getting a multi-year growth plan. As US-made products and supplies get increased priority from the federal government, moving those goods across the nation will require proper infrastructure to support truckers.

With pre-existing supply chain problems creating challenges in meeting domestic demand, inadequate nationwide truck parking only adds to the larger supply chain problem. Though this issue has been on truckers’ and transit organizations’ minds for years now, the compounding effects of the last few years are making it more important than ever to strategize on a solution.

The Scope of the Truck Parking Issue

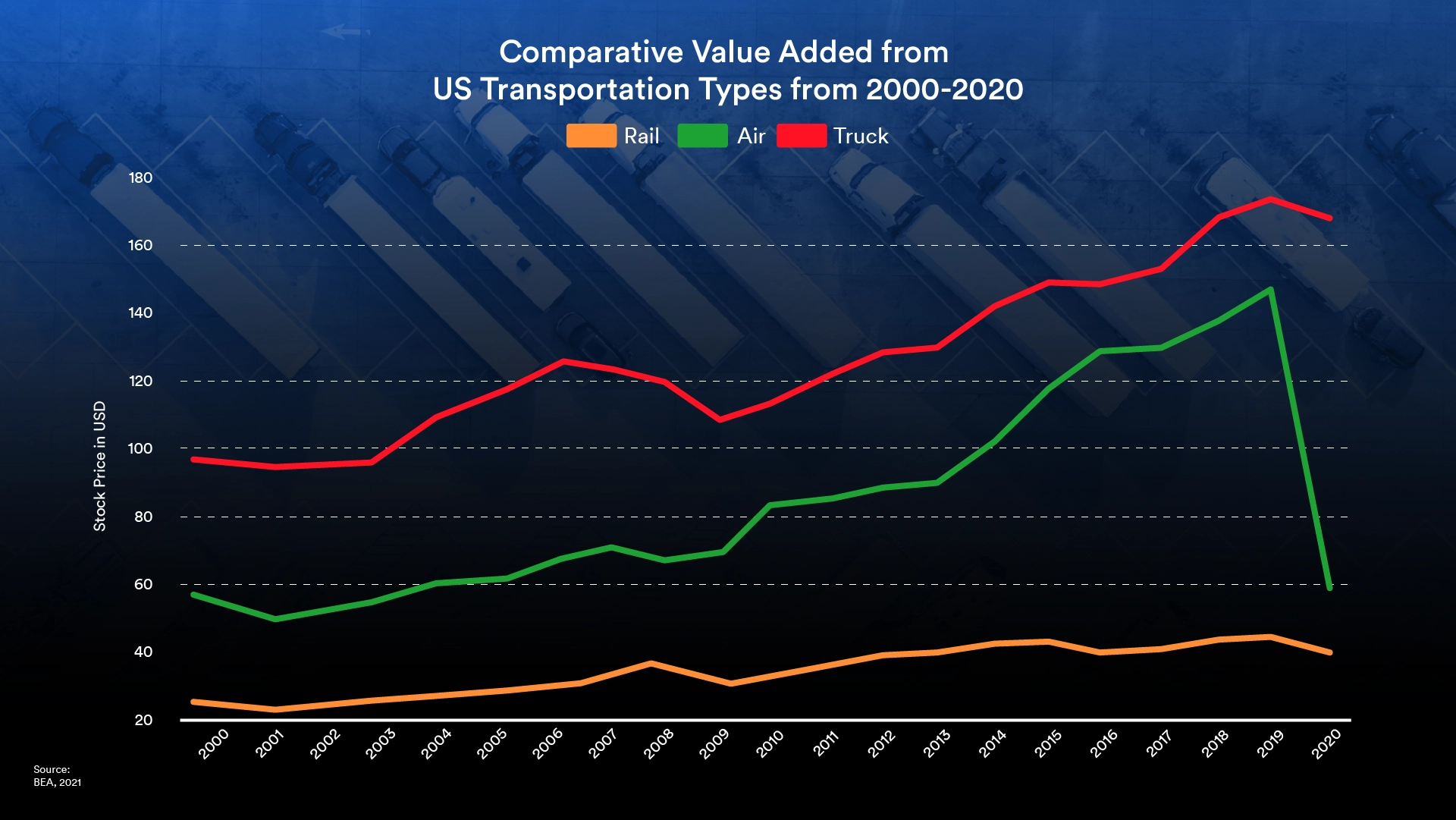

Trucks have been, and more than likely will continue to be, the main source of product shipment inside the U.S. in the coming years. The U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis calculated that the dollar value added from truck transportation has been steadily increasing over the past 20 years, providing over $150 billion in value each year over the last five years. Compare this to rail and air transportation value where air steadily remained under $150 billion and rail has yet to crack $50 billion. The graph above only covers the 20 years up until 2020, but the BEA’s most updated calculations, “Value Added by Industry,” reflect even more timely data from 2021 that supports this trend. If anything, 2021 further entrenched truck transportation’s value to the US economy, reaching $183 billion last year.

With such outsized value as an industry, and with such predictable consequences for drivers when parking is unavailable, finding solutions for this safety and logistical challenge becomes a no-brainer priority.

The most basic operational solution to curbing the worst effects of inadequate truck parking is to give truck drivers the infrastructure they need to rest and recharge away from passenger traffic. Truck drivers not only need a safe place to sleep at night, but also a way to pull off the road without competing for off-ramp space with small sedans. When truck drivers cannot find parking, it puts everyone at risk.

“They try to park in places that aren’t designated for trucks” Dr. Katsikides said. “These can be in places where they might mix with passenger vehicles, which is always dangerous because trucks are slower to ingress and egress than passenger cars. And a lot of times passenger cars will whip around the truck and cause some problems.”

Not only is mixing with passenger vehicles dangerous, but the variations in size and speed also create more traffic as trucks are stuck driving around urban areas looking for parking, thus causing delays in both city traffic and the larger supply chain.

“Take for instance the ports of LA and Long Beach. There’s no safe truck parking in and around the ports,” said Weston Labar, Head of Strategy for short-haul logistics company Cargomatic. “They don’t have the ability to drive those long distances and park in a safe place, creating issues in and around the port, both congestion and traffic related.”

In the context of our current supply chain woes, the consequences of additional travel time for truck drivers have already sent a ripple effect down the chain.

“It’s adding to the cost of doing business through added time and fuel,” said Dr. Katsikides.

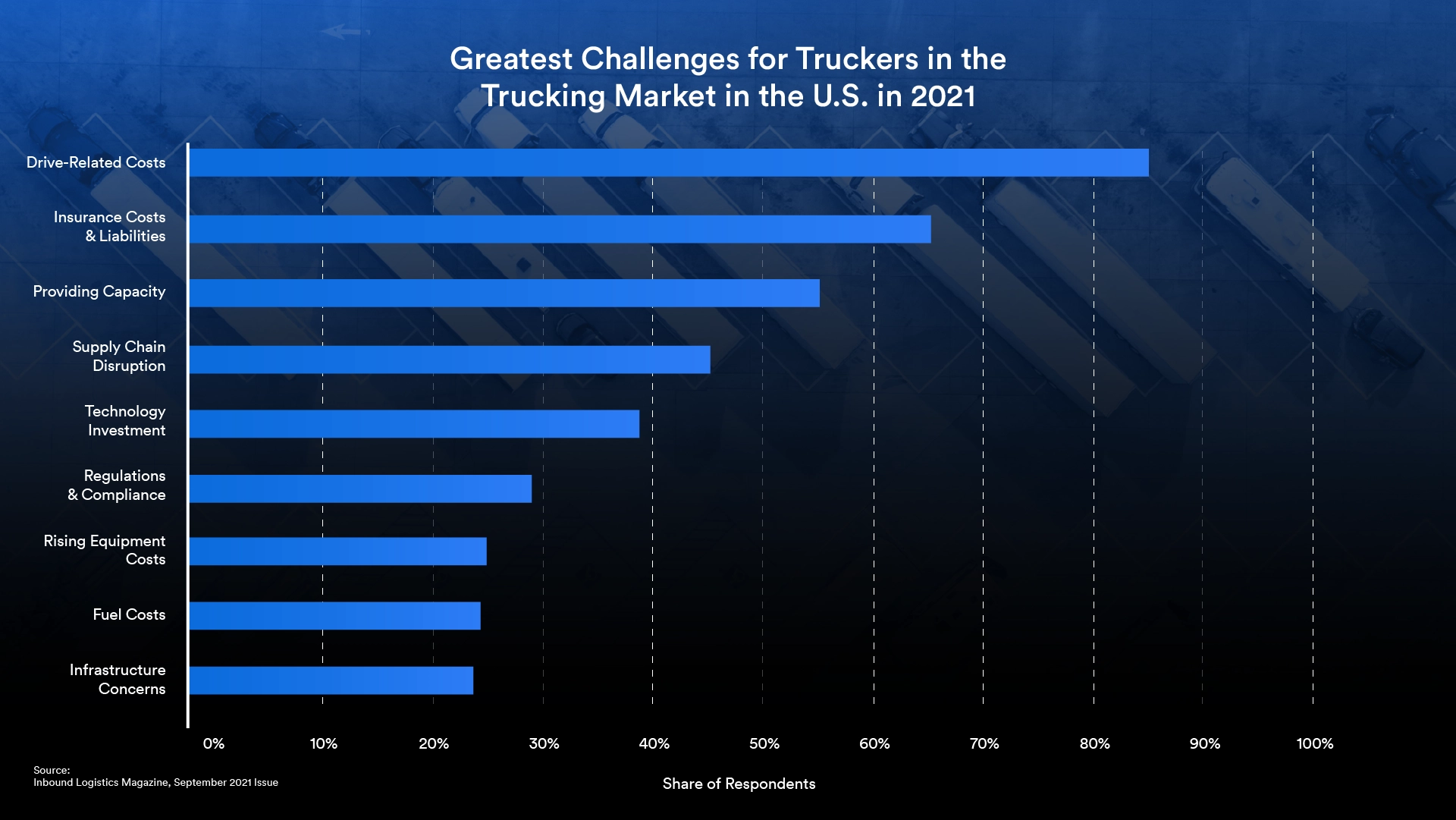

In the September 2021 edition of Inbound Logistics, 85% of drivers reported that the greatest challenge in the trucking market was “driver-related costs,” including equipment, maintenance and fuel, all of which cost more when drivers are diverting their routes and parking in hazardous locations. Coupled with the current spike in gas prices, increases in driver-related costs get passed on to the logistics companies contracting the drivers, resulting in a price hike of the delivered goods down to the consumer. The extra time and expenses tied to deliveries aren’t decreasing the relatively inelastic demand for their shipped goods. As of now, these costs are mainly subtracting from shipping efficiency, which in turn impacts retailers’ bottom lines, manufacturers’ access to raw materials, and product availability for consumers.

Persisting Problems, Stagnant Solutions

It’s important to remember that while truckers and trucking organizations push for federal funding support, this isn’t a new issue for drivers; it’s been one of the most unifying initiatives across the trucking community in recent memory. Since at least 2009, when truck driver Jason Rivenburg’s lack of parking options led him rest at an abandoned gas station where he was eventually killed, the trucking community has been vocal in demanding more truck parking funding, turning a grievance into a movement. High-profile calls to action over the years have included the 2010 release of popular trucking industry CD “When The Big Rigs Don’t Roll” with a song dedicated to Rivenburg and the need for safer truck parking, early legislative pushes from 2009 to 2012, the Federal Highway Administration’s 2015 study of truck parking, and constant online articles from the OOIDA and ATA calling for change since at least 2017.

Rivenburg’s untimely and preventable death culminated in a clearer step forward for understanding the scope of the issue. Hope Rivenburg, Jason’s wife, led a public campaign for the passing of Jason’s Law, enshrined as law in 2012, which requires a “survey of each State to evaluate parking, commercial motor vehicle traffic volumes, and to derive a system of metrics to measure truck parking in each State.”

The most recent iteration of the survey, released in 2020, highlighted the scope of the issue and the progress that’s been made since the passing of the law. Between 2014 and 2019, public truck parking spaces increased by 6% to around 40,000, and private truck parking spaces increased 11% to around 273,000. This is an improvement, but when put into context, the numbers reflect why there’s mounting frustration from the trucking industry.

Overall, the USDOT found that…

- “Not many new public facilities or spaces are being developed”

- “Challenges exist in planning, funding, and accommodating truck parking”

- “79 percent [of truck stop owners and operators] do not plan to add more truck parking”

- “New shortages emerged in additional locations since 2014”

- “Drivers reported challenges in every state and region, particularly along major freight corridors in States along I-95, the Chicago region, and I-5 in California”

As mentioned earlier, nearly all drivers reported having regular difficulties finding safe parking. This number increased in dramatic fashion from 75% in the 2015 survey to 98% in the 2020 survey.

Not only has the problem become more acute in certain US regions, but it’s clear that the funding infrastructure for new parking is functionally nonexistent at scale. What funding and state-level truck parking plans do exist tend to focus more on improved data collection, technology solutions, engaging stakeholders, and seeking public-private partnerships for creative financing strategies.

Stagnation around the issue led the ATA and OOIDA to make a more pointed call to action earlier in February with a direct letter to Secretary of Transportation Pete Buttigieg. The two organizations explained the layered consequences of continuing to ignore this issue and put the onus on Buttigieg’s department to push for and support more focused truck parking funds and to “educate state and local partners” on existing funding options.

Adjustments in strategy from all stakeholders, including the USDOT and its state counterparts, are a necessity to prevent further loss of efficiency in the industry. However, the solution to the truck parking problem does not come as easily as recognizing there is an issue.

Where Will Truck Parking Legislation Go from Here?

The big question weighing on logistics industry organizations and service providers is: If this issue is so pressing, why has the US Department of Transportation done little to proactively solve this problem and why is there no designated funding for them to do so? Dr. Katsikides, who previously worked for the Maryland DOT, didn’t shy away from highlighting the deficiencies that transportation bureaucracy creates in solving mounting and expensive challenges.

“They have many, many things that they have to do, and putting the truck parking development onto busy state DOT people who don’t have a lot of experience developing truck parking is not a very efficient process,” she said.

The Biden administration is aware of the importance of funding infrastructure projects, as seen with its landmark Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act. For transportation infrastructure, the administration’s focus has been on another historically underfunded sector: road conditions, which also contribute to the challenge for truck drivers to deliver goods efficiently, safely and on time. The American Society of Civil Engineer’s 2021 Report Card for America’s Infrastructure gave road systems throughout the nation a ‘D’ letter grade. Almost half of the roads, an estimated 43%, are either in poor or mediocre condition. The Biden administration’s Bipartisan Infrastructure Deal will invest billions toward fixing of roads, reconstructing bridges, revitalizing highways, building EV chargers, and building out new passenger rail and other public transit modes.

While it’s positive that the government sees current road conditions as a concern for the US’ citizens and its economy, nowhere in the Bipartisan Infrastructure Deal is there clear funding for truck parking. Frustratingly for industry professionals, the House version of the infrastructure bill originally had a provision for $1 billion exclusively for truck parking projects. Once the bill was revised by the Senate and made it into law, that provision was dropped.

Instead, the final bill provides major increases to bulk spending accounts where truck parking is one of many possible expenditure choices. These include…

- Surface Transportation Block Grant Program

- National Highway Freight Program

- Highway Safety Improvement Program

- National Highway Performance Program

- Congestion Mitigation and Air Quality Improvement Program

This funding is welcomed, but the uncertainty around whether these funds will go to truck parking leaves the successful implementation of these funds up to several variables, including the whims of state and local legislators. The ATA and OOIDA called this out in their letter to Secretary Buttigieg, urging his department to train stakeholders and encourage them to “prioritize funding for grants that would increase truck parking capacity.”

It’s clear that there’s a lack of federal funding in areas where federal funds should be prioritized, especially if infrastructure spending is already a top priority. Some legislators are working to align federal priorities with federal funding, taking up the mantle of creating a focused truck parking fund.

Introduced in March 2021 by Rep. Mike Bost, R-Ill., the Truck Parking Safety Improvement Act is aimed at establishing a $755 million fund specifically for truck parking infrastructure, allocated over five years and pulling from the already-established Fixing America’s Surface Transportation Act and the Highway Trust Fund.

The bill is still sitting in limbo and has been since its introduction in March, slowly integrating more legislative support. Signs point to the bill being more of a priority for Congress, though; likely due to a mix of high-profile discussion from the ATA and OOIDA as well as compounding negative effects of supply chain disruption, June 2022 proved to be the largest single-month increase of co-sponsors since May 2021, adding four new representatives to the bill.

The bill now totals 36 co-sponsors in the House of Representatives. The most recent additions include Reps. Jaime Herrera Beutler, R-Wash., and Troy Nehls, R-Texas.

Even beyond the Truck Parking Safety Improvement Act, Congress is raising the truck parking issue among legislators and administration leaders, signaling truck parking may be a major ticket item for the House moving through the rest of the year.

During a recent Highways and Transit subcommittee hearing, Rep. Peter DeFazio, D-Ore., made urgent calls for increasing funding for truck parking, pushing for Secretary Buttigieg to put existing grant programs to work for new parking infrastructure, like the Infrastructure for Rebuilding America (INFRA) fund and the Rebuilding American Infrastructure with Sustainability and Equity (RAISE) fund.

Safety is a major factor in why providing adequate national truck parking has been placed on the list of priorities and gained renewed federal interest. As of May 2022, “fatalities involving at least one big truck were up 13%,” reported Tom Krisher for Transport Topics. Another study, the Texas Statewide Truck Parking Study cited by Rep. DeFazio and Rep. Sam Graves, R-Mo., in their letter to Secretary Buttigieg, found that from 2013 to 2017 the number of crashes involving parked freight trucks reached 2300 with 138 fatalities.

Road conditions, as mentioned earlier, are in poor condition, while the number of people on roads are increasing, leading to more traffic and risk of accident. Data from the NHTSA shows predicted traffic fatalities increased by 18.4% from 2020 to 2021, the highest it has been in 13 years.

From drivers to industry organizations to legislators, it seems that critical stakeholders are more driven than ever, pun intended, to find a strategy that creates necessary additional parking for trucks; how, then, does the industry turn need into action?

Finding Solutions Will Take Public-Private Alignment

The brightest hope for more truck parking infrastructure is seeing HR2187, the Truck Parking Safety Improvement Act, through to the end. Moving it forward in the House will take more legislative pressure from co-sponsors and the consistent input of drivers and industry organizations. Advocates of HR2187 have called on truckers, organizations, and even companies with an outsized reliance on trucking logistics to vocalize their stance to their House representative.

Bill advocates point industry professionals to FightingforTruckers.com to identify their representative and send them an email in support of the bill.

Unfortunately, the solution to a lack of adequate parking is often presented solely as ‘better driver strategy,’ framing the solution as the individual responsibility of each driver. ‘It’s up to drivers to make the safest, most efficient, and most practical decision that keeps them, their truck and their cargo safe in the short-term,’ for example.

Until parking infrastructure is built out, drivers can prioritize mapping out their routes more proactively, using several truck parking apps, and communicating with their clients/employers about route needs and safety concerns. OOIDA’s EVP Lewie Pugh, though, sees this driver-onus narrative as dated and ineffective to solving the issue.

“A trucker’s day constantly changes. Unexpected weather, traffic, accidents, delays in loading and unloading and road construction are just some of the things truckers encounter through no fault of their own. Finally, none of these things matter if the number of trucks exceed the number of parking spaces,” Pugh said, as reported in Land Line.

In terms of potential strategies for getting proper infrastructure funds flowing, Dr. Katsikides sees a multitude of strategic initiatives for change, including having key stakeholders push for reallocating existing federal and state funds toward parking projects. Regardless, she sees stagnation and red tape around meaningful US government action as an inhibitor.

“There may be lots of different options. I think it’s critically important that industry understand the challenges that when funds flow through the public sector, what the public sector has to face, the procurement laws, the transparency, and accountability that’s involved and how everything has to be done a certain way,” she said.

Of course, following regulatory protocol is an important part of any potential federally funded solution to improve truck parking, but as with any public initiative the time needed for the approval and building of any new parking lots delays solutions while the problem grows. The 2020 Jason’s Law Survey also reminded us that an overwhelming majority of private rest stop owners and operators have no interest in expanding their number of parking spaces.

As zoning laws continue to be another local inhibitor to progress by either cancelling projects or slowing them down, the need for safety-focused truck parking strategy will remain pressing.

“The local governments need to be better at zoning, to allow for the supply chains to move efficiently. State governments need to identify places throughout their region where they can have safe, regionalized truck parking that allows the community, the supply chain community, to service the multiple nodes in the most efficient manner. And the federal government needs to look at this type of infrastructure as a critical infrastructure, the way they do with roads and bridges,” Labar said.

Even if local governments wanted to move the needle faster than their federal counterparts, municipalities often don’t have enough of a budget or the workforce needed to focus on building out truck parking.

“Some of the [solutions] that I’ve been working on are maybe the state contributes property or funding and a private entity can develop or work through the local zoning laws to come up with parking especially off major freight corridors. And then I also recommend working with economic development entities,” Katiskides said.

For example, major cities like Philadelphia have sectioned key areas of focus in their estimated capital budget, and yet nowhere does the city allocate funds to truck parking despite Pennsylvania being one of the states identified as having the “most severe challenges” in a lack of truck parking. The city of Philadelphia has estimated $278.1 million to go into infrastructure projects like resurfacing of streets, bridge restoration, and city reconstruction. Allocating even more funds for truck parking is unlikely; the city is stretched thin and like most municipalities lacks the strategy for how to prioritize truck parking. According to Dr. Katsikides, it sounds like the same is true for the USDOT.

“So, it gets down to how can industry really help the state DOT or local government understand how to develop parking on top of all of their other responsibilities and how to use the federal funding in the best possible way to develop this,” said Katsikides

In May, Noёl Fletcher from Transport Topics reported that the American Transportation Research Institute has been in support of the Transportation Research Board working on truck parking guidebooks in hopes of providing guidelines and education to all states and local governments on how to fund these projects. These guidebooks will be composed of proprietary research as well as survey responses from truck drivers; the ATRI’s newest survey for drivers to help state DOTs “best coordinate real-time truck parking information for most major corridors in the Midwest” closed as recently as June 24th.

If these materialize, the guidelines created for state and local governments could help tremendously by explaining the importance of truck parking as well as the best strategies for creating strategically-placed infrastructure, considering many state DOTs have little experience with projects such as truck parking development. Regardless, prioritizing a solution is in the whole country’s best interest.

“It’s truckers who are moving the nation’s goods and it’s the nation’s goods who truly impact our nation’s economy,” Labar said.

In summary, after the release of its 2015 Jason’s Law Survey, the FHWA highlighted its key goals for materializing a nationwide solution for needed truck parking. Considering how little the problem has improved since then and considering that federal and state decision makers still need to design and implement achievable action plans at large, these FHWA goals remain a guideline for the whole industry:

“The FHWA intends to continue to work with public and private stakeholders to advance the availability of adequate and safe truck parking. Activities targeted for partnership include assisting stakeholders in improving the state of the practice for evaluating truck parking needs, working with stakeholders to support incorporating truck parking into relevant transportation planning such as State freight plans and regional or corridor plans, and encouraging continued discussions among stakeholders.”