Analysis: Lessons for CEOs from the Schultz & Starbucks Union Avoidance Campaign

Summary: In this report, corporate executives will get a full analysis of Starbucks’ union avoidance saga since the return of Howard Schultz, detailing his strategies over the years, how he’s putting them to work now, and how the consequences of taking an aggressive stance against Starbucks Workers United have impacted the company’s brand and financials. Citing several retail and labor experts, this report will offer a pulse-check on why Schultz’s tactics are being poorly received, and will distill these reactions down into actionable strategies for leadership to more proactively engage with union campaigns.

Table of Contents

- What Does Starbucks Want Out Of Its CEO?

- Schultz’s Union Avoidance History and Strategies

- Starbucks Workers United’s Demands for Schultz

- How Schultz is Trying to Stop a Starbucks Union This Time Around

- Why Starbucks’ Union-Busting Tactics Aren’t Being Well-Received

- As CEO, Who is Schultz Responsible To?

- Should CEOs Fear Unions?

- Final Words of Advice for CEOs

The last two months for Starbucks have been transformational ones from the top-down and the bottom-up. When its five-year CEO Kevin Johnson announced he was stepping down in mid-March, the company was already facing a labor reckoning unlike anything it’s seen in years. Starbucks workers, who since the start of the pandemic have renewed their calls for increased worker protections, better staffing and fairer wages, took matters into their own hands with a watershed movement: the creation of Starbucks Workers United and the company’s first unionized store in Buffalo, New York.

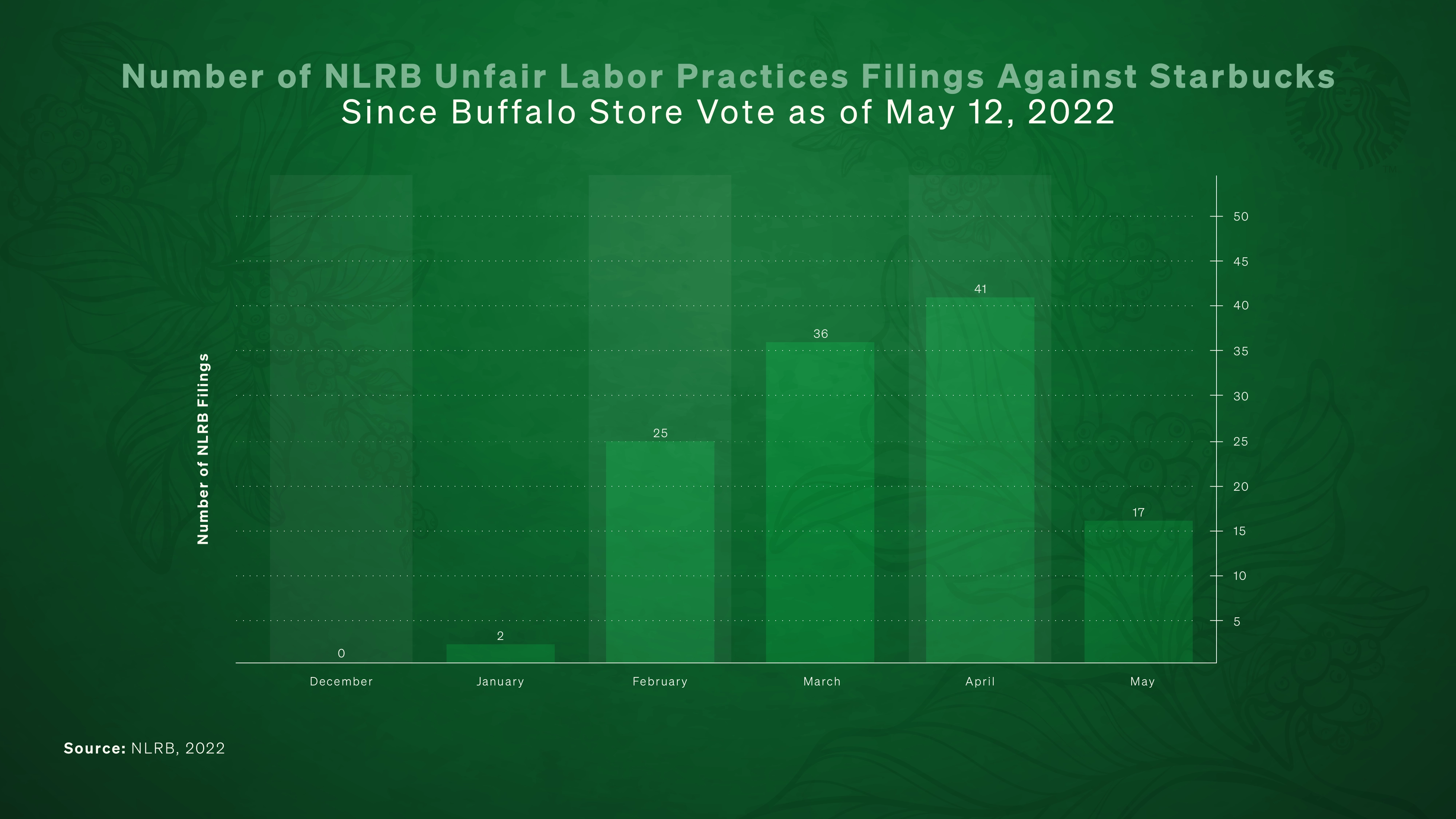

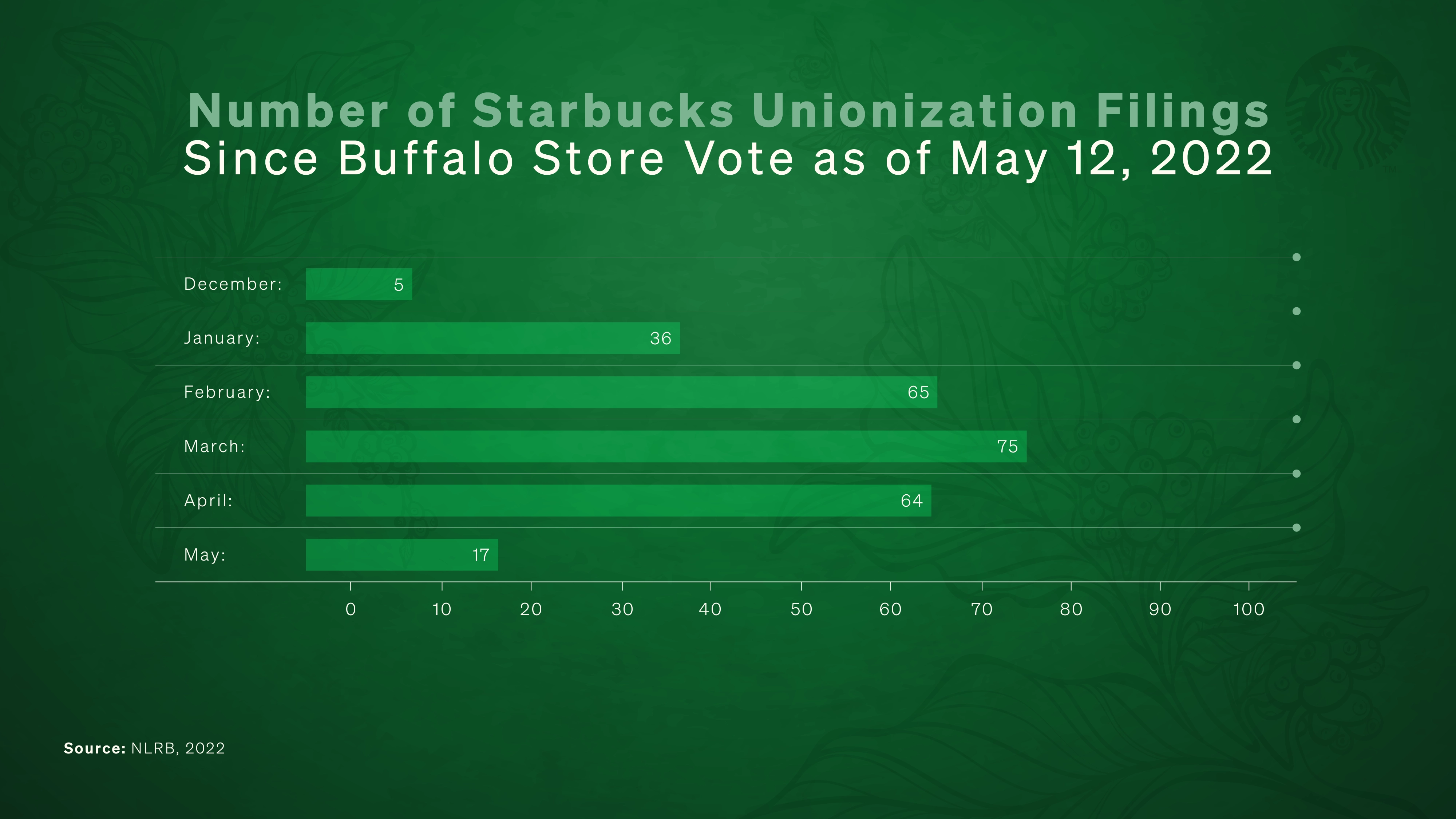

By mid-March as Johnson left the company, Starbucks had around 140 stores petitioning to the NLRB for a unionization vote, with six stores already voting in favor of a union. This was all in the span of a few months. The movement, and subsequent pressure on Starbucks, has only grown. As of May 12, there are more than 260 stores seeking a union vote, with more than 60 stores logging a majority ‘Yes’ vote according to NLRB and LAW360 data. This is reflective not only of the specific issues baristas have with Starbucks, but also issues that COVID created for the retail environment.

“All of these disruptions happened in the macro environment. Workers in retail wanted to work in a safe environment, and also not only in terms of pay, but also in terms of benefits. And so what we are seeing in Starbucks is not an isolated event,” said Venkatesh Shankar, Ph.D., Director of Research for the Center for Retailing Studies at Texas A&M University.

Like most companies of its stature, Starbucks has been resistant of a labor movement within its stores since the start of this renewed campaign. It’s no secret that Starbucks views a union as a disruptive force.

“From the beginning, we’ve been clear in our belief that we do not want a union between us as partners, and that conviction has not changed. However, we have also said that we respect the legal process,” wrote executive vice president Rossann Williams after the Buffalo union win.

The reasons for Starbucks not wanting a union will be explored more in-depth throughout this report, but for starters, let’s briefly frame the Starbucks union movements against the state of the national economy. Shankar’s analysis paints a picture that makes unionizing, and the potential operational consequences of increased labor costs, the last thing Starbucks wants to worry about right now.

One of the chief concerns of the moment for retail and food service companies is how consistently-rising inflation is going to affect sales; the most recent inflation report has the CPI 8.3% higher than April of last year, a steady climb since May 2020. A survey of almost 4000 Americans shows discretionary spending is likely to recede, if not declining already, with 52% of respondents indicating they’ll “cut back on dining out” if high prices persist, the largest share of consensus in the survey. Expensive coffee, or as Shankar calls it, “not Starbucks but four bucks,” is probably on that list.

Adapting to this moment as a unified company is critical. Starbucks sees a union as a threat to that unity, especially if short-term quarterly sales decline as workers demand more in compensation.

“There are some price points, psychological price points, beyond which if you have any item that is charged more than five bucks now people will stop buying even the things that they were buying before. And so it is important for [Starbucks] to work with their employees,” Shankar said. “And unless they do that, I see that this unionization trend will keep continuing and it will be hard for them to stop them just by their regular playbook.”

Starbucks is also a rather agile company, known for growing quickly and implementing radical shifts in company strategy.

“Companies like Starbucks, Amazon, they’re really highflyers and fast growers and not being used to a situation where they had to really go through another stakeholder to approve of all the major decisions,” Shankar said. “Once you go through the union, the decision-making slows down considerably.”

While Starbucks workers organized, the Starbucks Board debated the best course of action for engaging with a labor movement. It appeared a change in management was in order as one CEO exited the stage and another stepped in to fill old shoes, with tenured ex-CEO Howard Schultz returning to the helm of the company. In his announcement letter, Schultz made it clear that he wanted his interim period as Chief Executive to be focused on the “collective success of all our stakeholders.”

“My first work is to spend lots of time with partners. To lift up voices. To see everything that is already in play to help us become this kind of company. To invent. To face challenges — and for us each to be transparent with one another and become accountable for building the future of our company,” Schultz wrote.

Nowhere in the letter did it explicitly say the words ‘union’ or acknowledge the movement, but a promise of open communication and grassroots engagement from Schultz and Starbucks leadership hinted at where his focus as a returning CEO would lie: outreach to baristas in an attempt to get in front of a unionization campaign.

Facing a union campaign head-on is a match-up familiar to Schultz, even rather recently. On his first day back as CEO, he reiterated his stance during a town hall on one of the company’s perceived keys to success: “We didn’t get here by having a union.”

In February, the company expanded on its convictions in a more complete way with a detailed webpage dedicated to its stance on unionizing and why it thinks it isn’t a fit for Starbucks.

“Simply put – we are better side-by-side. We will build a better experience working side-by-side than by sitting across a negotiating table,” Starbucks said on its site.

Side-by-side is Schultz’s style as a leader, for better or for worse. Whether he’s embraced as Uncle Howie or critiqued for a paternalistic leadership style, there’s a common thread between how baristas and store managers describe Schultz. He’s vocal about his social and political worldview, and it gets passed down to baristas through company initiatives (some better received than others). He’s been an ever-present CEO in daily operations through frequent store visits, public showings and copies of his memoir for sale in-store (of which baristas receive a partner edition). His humble beginnings, all-smiles personality and working class come-up story are the backbone of Starbucks’ intended socially-conscious mission and a key part of the Starbucks mythos, especially internally.

“You know, I’m not putting myself in the class of Tom Brady or any other athlete that has been at the cornerstone of success on a team sport. This is a team sport. It has always been a team sport. I’ve gotten more credit that I deserve,” Schultz told CNBC in an interview as he was stepping down for the second time from Starbucks leadership in 2016.

When the union pressure increased, Starbucks turned back to Schultz for answers, direction, and strategy that would reconnect the company with its workers. But after reviewing the current state of the company’s union movement, was the Schultz Decision the right one for Starbucks? The pace of new union elections is still high, and everything from Schultz’s new benefits packages to his direct anti-union language haven’t done much to dissuade the movement. Though Schultz has curated his brand as the vocal do-gooder CEO, his vocal anti-union stance has left a coffee stain on his reputation with some baristas.

What are the learning lessons for CEOs from this entire Starbucks union saga?

The return of a familiar CEO with familiar union-busting attitudes prompted us to do some analysis for companies and leaders asking themselves how they’d handle being in Starbucks’ shoes. Chatting with labor and retail experts, reviewing Schultz’s words and actions during the campaign, reading through perspectives from both sides of the labor aisle (from unionizing Starbucks workers to The Heritage Foundation), and consulting studies from various academic sources, this analysis offers some perspectives on how a modern company and a modern CEO should approach a unionizing campaign in the current social climate. Based on how Schultz’s commentary and action has manifested during the current Starbucks Workers United movement, it’s become clear that companies shouldn’t underestimate the weight and appeal of a reinvigorated labor movement, nor the consequences of how they respond.

“I would encourage, not just Mr. Schultz, but I would encourage any CEO right now, pay attention to what your workers are telling you about your workplace,” said Robert Bruno, Ph.D., Assistant Professor of Labor and Industrial Relations and Director of the Labor Studies Program at the University of Illinois.

What Does Starbucks Want Out Of Its CEO?

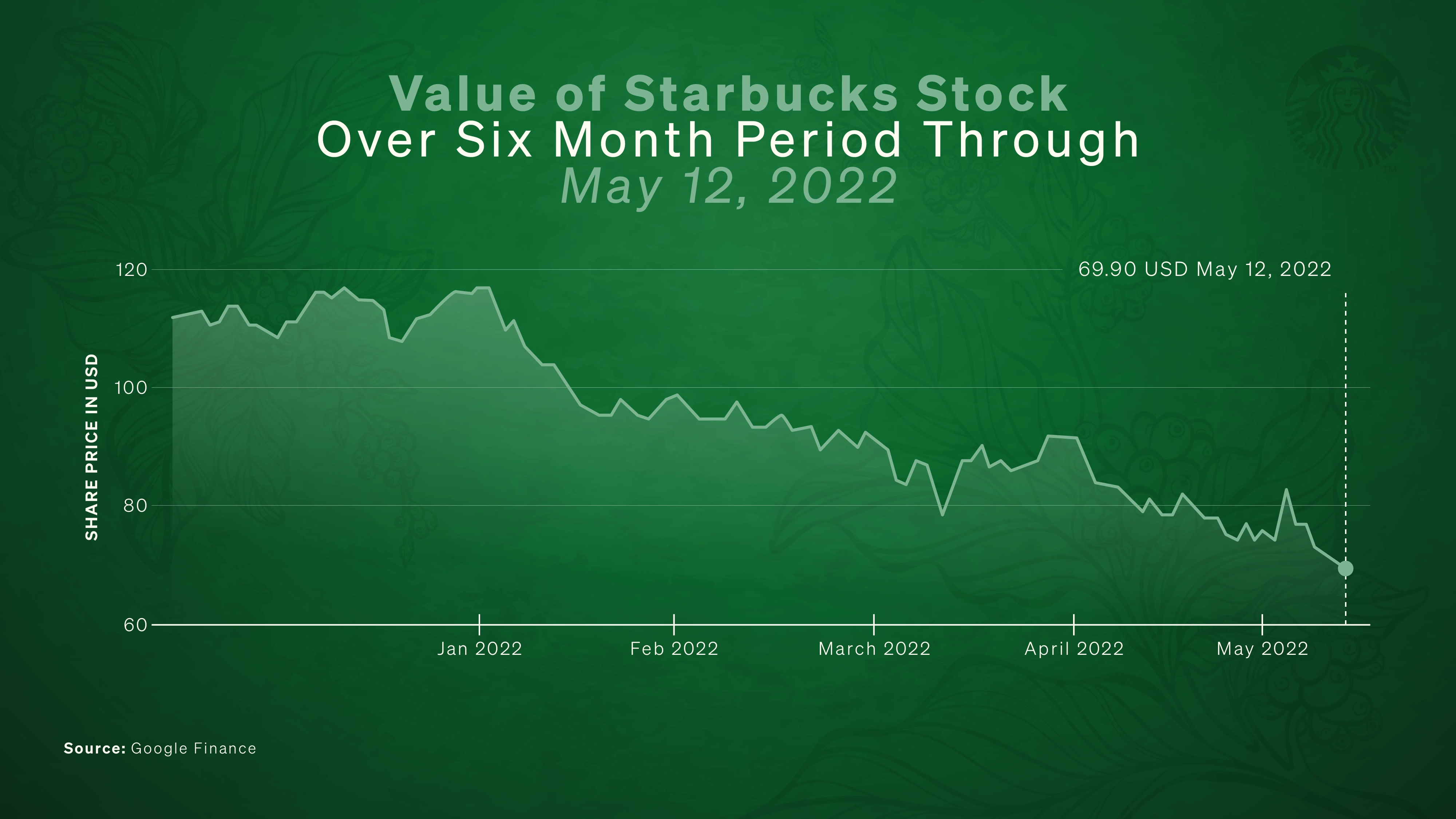

Since Starbucks workers won their first union vote, Starbucks’ stock has been on the downslope. The fragile state of today’s national economy is placing fresh pressure on CEOs like Schultz to deliver on several metrics for vested capital interests. One of those metrics includes keeping the company as profitable as possible, which usually coincides with keeping union sentiments at bay; as one unaffiliated CEO put it, seeing a union movement at his company dissolve inspired “relief.”

“At some point during training, executives learn this lesson that, if you let your company unionize, it’s dead and you personally don’t have a future because you’ve committed the greatest cardinal sin that American management could create: You’ve let your company be unionized,” said Paul Clark, Ph.D., Professor and Graduate Program Director for the School of Labor and Employment Relations at Penn State University.

Is a CEO’s job security judged on how they deal with unions? Let’s explore the Starbucks situation as an example. The leadership change and its timing surrounding a renewed Starbucks labor wave drew questions around why Johnson stepped down in the first place, including whether he faced pressure from the Starbucks Board and its shareholders due to his inability to curb unionizing energy. Some of the labor experts I spoke to seem to think so.

“What mattered to the board and why a leadership change was announced is that workers are agitating and organizing into a collective force, and nothing threatens the company’s appeal to investors and cherished progressive image more than having democracy break out in the workplace,” Bruno said.

Neither party is likely to confirm the complete reasoning behind Johnson’s exit, so we remain in a realm of speculation, though we can make some educated inferences.

When Starbucks announced Johnson’s transition, he apparently already had an exit on the mind for over a year. His goodbye statement revealed he made this known to the Board, that “as the global pandemic neared an end, [he] would be considering retirement from Starbucks.”

Mellody Hobson, the chair of Starbucks’ board, reiterated this narrative during the company’s annual meeting of shareholders, saying that Johnson “signaled to [the Board] early last year that he was starting to think about his future and possible retirement.”

“Considering” and “starting to think about” aren’t quite the same as ‘confirmed’ or ‘planned,’ but let’s take this at face value: Johnson and the Board previously arranged to have him exit the company. Hobson explained to shareholders that the company formed a working committee after hearing of Johnson’s retirement ruminations, was on top of selecting a permanent replacement by the fall, and that there were already promising candidates lined up.

This narrative has some inconsistencies. If the Starbucks Board and Johnson were already planning to have him step away as CEO, why did his exit come as such a surprise; why was this the first time all shareholders were made aware of a succession plan? If this was on the working committee’s radar for over a year, why are they still in the search process for a new CEO (consider most executive searches take around seven or eight months, and other major food brands like Dominos and Wingstop that announced CEO transitions around the same time already had a successor picked)?

If Starbucks was confident in its permanent replacement candidates, why pull the plug on Johnson early and bother with an interim leadership period? This isn’t to say there was a grand conspiracy to keep his exit hush-hush, but rather that it puts a magnifying glass on the specific timing of Johnson’s retirement. As more time passes and Schultz’s leadership tactics manifest, Johnson’s move reads more like an unanticipated early exit spurred by growing union sentiment that he wasn’t cut out to quell.

The biggest clue to back up that take is also the most straightforward one. As Schultz was publicly welcomed back by the company, Hobson did a round of interviews with business news media. In her CNBC sit down, she was asked about the current union movement and the company’s strategies for engaging with workers. In her answer was a revealing perspective on why the company turned to Schultz during this unprecedented labor wave.

“When you think about, again, why we’re leaning on Howard in this moment, it’s that connection with our people and where we think he is singularly capable of engaging with our people in a way that will make a difference,” Hobson said.

If Starbucks’ actions are to speak for themselves, ‘making a difference’ doesn’t mean more unions; Hobson and the Board desired a change in organizing results with Schultz as the company’s leader. She made this clear when explaining why the company didn’t want to take the path of a neutrality agreement with the union.

“On the specific issue of neutrality, this one is more nuanced. One would say, how could you be against neutrality? But neutrality in its nuanced form limits our ability to speak to our partners in certain ways,” Hobson said to shareholders in their annual meeting.

So then, if Schultz is at Starbucks to engage with baristas and “make a difference” but isn’t committing to a neutral approach with the union, a difference for whom and for what purpose? An anti-neutrality stance doesn’t mean the company won’t offer some material improvements to workers, but it won’t be in the way unionizing workers want it despite Hobson saying she wanted to build a “constructive relationship” with the union.

Based on Schultz’s actions over the last two months, it appears Starbucks sought the goal of offering enough non-union incentives and reshaping the conversation in a grassroots way to keep the union’s influence limited and put a hamper on its spread. Hobson and the Board placed their full confidence in Schultz as being “singularly capable” of pulling this off. This backs up the notion that Schultz was brought back for the express purpose of stopping the union train in its tracks, and Schultz being singularly capable of shaping this moment in Starbucks’ favor implies that Johnson wasn’t.

Consider, too, that while Johnson was CEO and workers started organizing in Buffalo, he took a more backseat role in vocally opposing the union, letting executive vice president Rossann Williams hold the metaphorical megaphone instead. As the fervor for a union became inevitable in Buffalo, who did the company send to talk to workers face-to-face? Not its CEO, Johnson, but its legacy leader, Schultz.

Under Johnson’s tenure, Starbucks achieved several milestones that gave it strong footing in a digital era and expanded its international footprint. Though, as Schultz explained earlier, this is a team sport and more than just the CEO deserves credit for these wins, some of the successes under Johnson include…

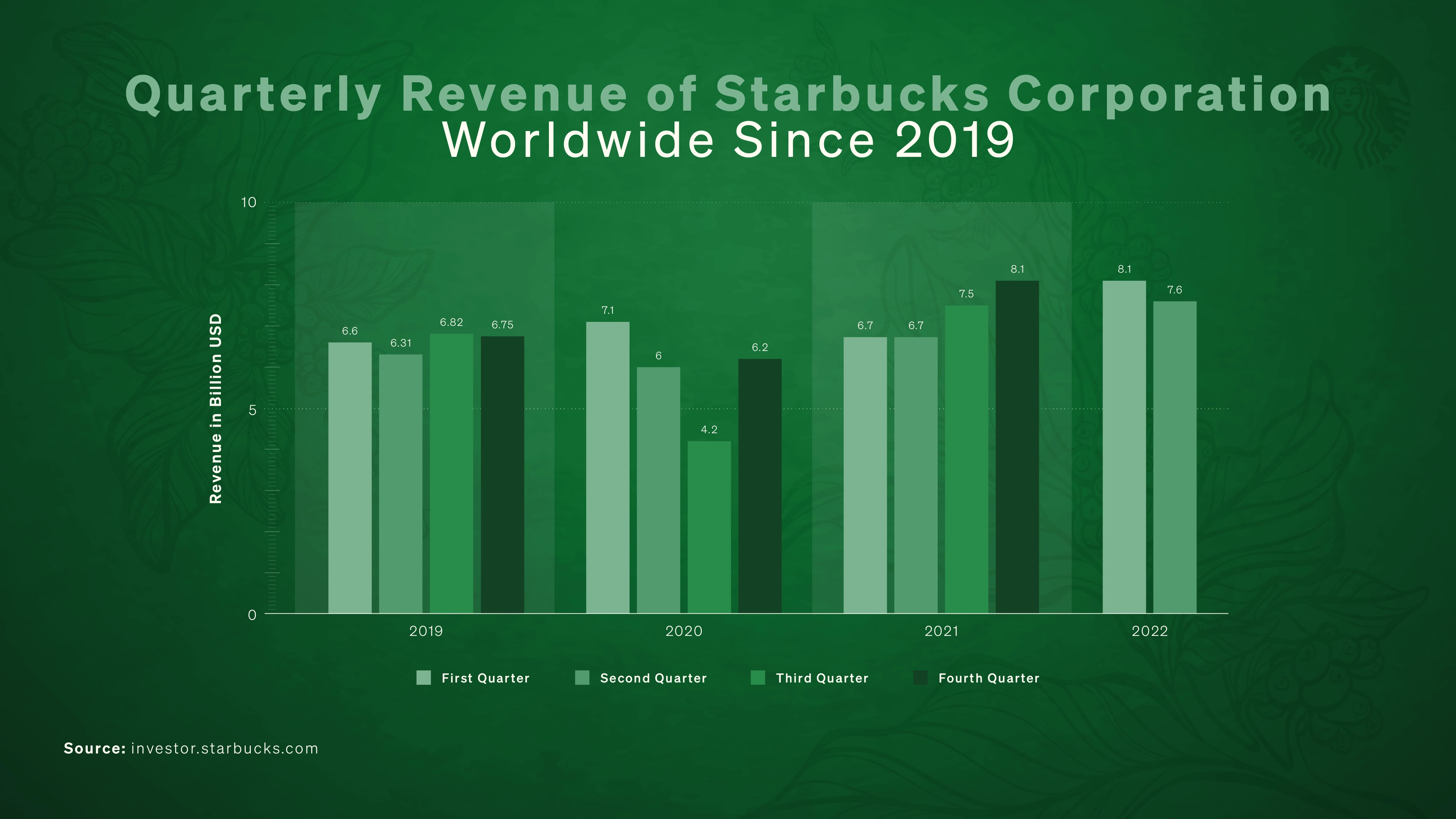

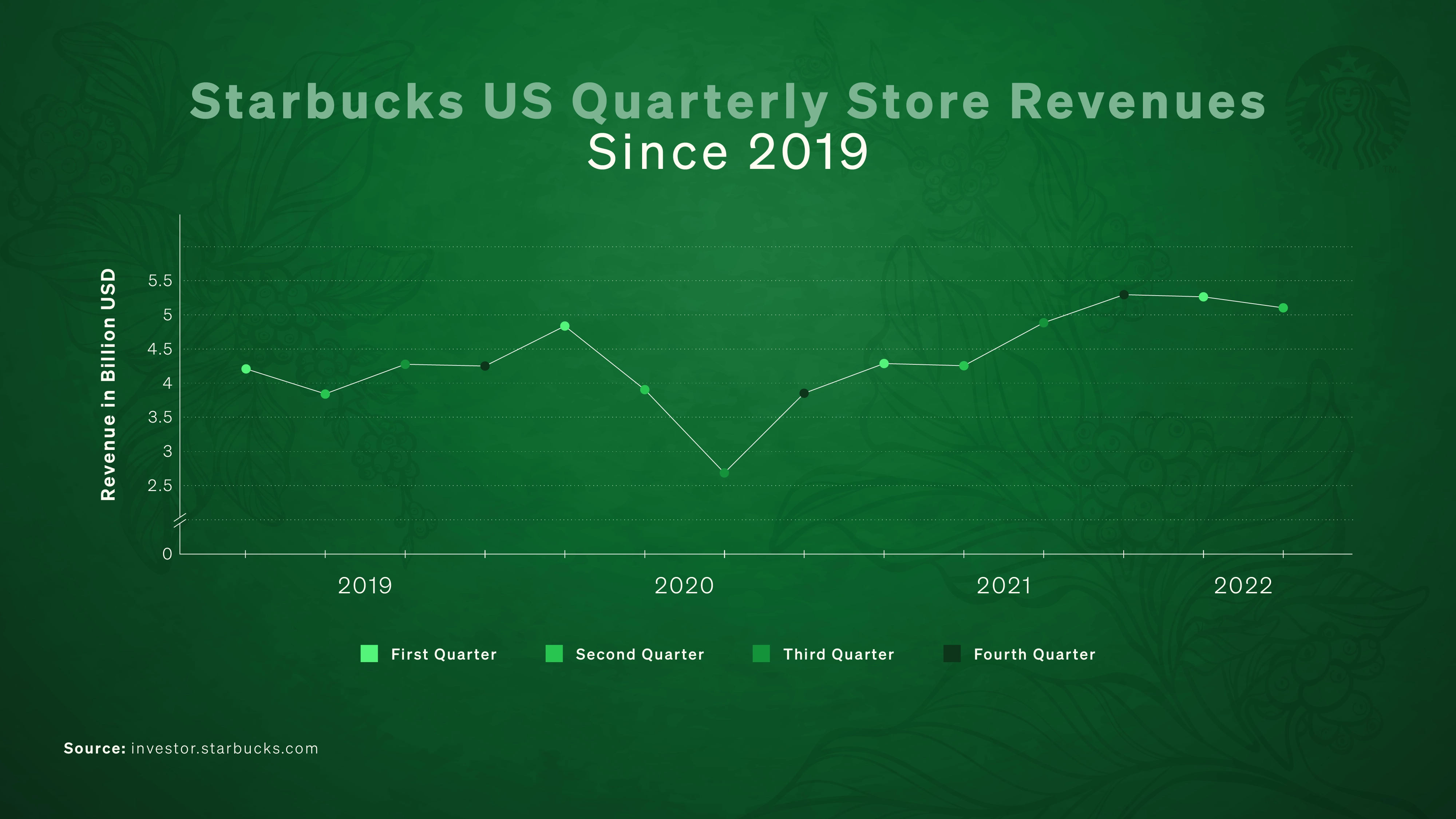

- maintaining profitability for the company through the pandemic and rebounding to bring back lost revenue, consistently beating quarterly year-over-year revenue records every quarter since Q2 2021

- using machine learning to grow the brand’s loyalty program, Starbucks Rewards, from 13 million active users in 2016 to 26.7 million in Q2 2022, a 17% increase from the year before

- leveraging the complete disruption of COVID to Starbucks’ advantage by leaning into the company’s digital intersections, including mobile-focused brick & mortar stores for pick-up only and pushing its already strong loyalty program presence to the point where 53% of spend in stores happened on Starbucks Rewards in Q1 2022

- moving the brand closer to full penetration of the Chinese market (6000 stores by 2022) through a strategy of opening a new store “every 15 hours for the next five years,” reaching 5,654 stores in Q2 2022 despite consistent COVID lockdowns slowing international sales

- expanding Starbucks more confidently into the CPG market through a Nestlé partnership, allowing the company to “market, sell and distribute” Starbucks’ various coffee and tea products

“During his tenure, Kevin expanded the company’s reach through the Global Coffee Alliance with Nestlé, which now operates in nearly 80 markets,” Hobson said.

Johnson’s leadership and strategic vision for Starbucks’ modern competitive edge played a role in taking the company from $59 a share at the start of his CEO run in 2017 to a peak of $126 a share in July 2021, settling in pre-Buffalo union vote around $115 a share. All in all, it amounts to around a 50% increase in share value. This post-mortem is to say that, even if Johnson was planning an exit for more than a year, his performance on most financial KPIs was strong. It’d be hard to say that Johnson was pressured to leave because he steered the company in an unprofitable direction or dropped the ball on the Board’s metrics.

Therefore if the narrative that he had been planning all along to leave in March has some holes, and if poor company performance is hard to argue as a motivator for swapping leaders, then one of the few errors left on Johnson’s track record was failing to proactively anticipate and prevent the spread of union sentiment. Taking all of the puzzle pieces into account, a speculative conclusion comes into focus: Even if Johnson and the Board had an exit planned at some point, his retirement came a bit earlier than expected and it was the rising unionization campaign that inevitably gave him an early boot.

“Especially when you’re coming out of the pandemic and the chain wants to go back to its more profitable and growth ways, it’s very imperative for the management to have its employees on board in all its growth ventures. And it is not in their interest to see unionization trying to put a damper on that,” Shankar said.

Seeking a new (or an old) type of leader to carry the company through this saga brought Starbucks back to the feet of its most famous spokesperson. Hobson made a bold prediction as Schultz returned to the company, that he was “singularly capable” of meeting this moment head on and creating positive results for the company. Is her prediction coming true?

Schultz’s History of Opposing Unions Highlights His Go-To Strategies

The final results of Schultz’s strategies toward the SWU movement won’t bear fruit for a while, so this analysis will only be a pulse-check reflecting on the company’s tactics and Schultz’s own actions up until now. With that said, unfortunately for Schultz and Hobson, his strategies have not had their intended effect. Starbucks unionization filings remain up, with recent wins in Tallahassee, Florida and Grand Rapids, Michigan. The announcement of expanded benefits for Starbucks workers hasn’t dissuaded them from consistent call outs of their difficult working conditions as well as of Starbucks’ response to the union.

Gauging how much of this continued worker sentiment is due to Schultz’s unique missteps versus a reflection of the times is up for debate. A reinvigoration of the labor rights fight is a trend capturing the imagination of workers across retail stores, from Amazon, to Apple, to REI, to Dollar General.

“It is a movement and we are not seeing just an isolated phenomenon. This is not the last time we are going to see it,” Shankar said. “Retailing was losing a lot of workers and not only because of the pandemic, but also workers not being able to meet the challenges of their customers even if they went to the workplace.”

But just because COVID massively disrupted the retail space and shined a light on gaps in the employee-management relationship doesn’t mean those gaps weren’t there in the first place. Starbucks itself is hesitant to say the whole SWU movement is COVID-related, either.

“We’re not hanging on COVID as an excuse. We made some mistakes here. We didn’t listen,” Hobson said in her CNBC interview.

Starbucks and Schultz’s anti-union strategies come in many different forms: telling baristas in Buffalo to vote ‘No’ on unionization, new benefits and higher pay, active denouncing of the union, allegedly firing organizing baristas, sit-down collaboration sessions with workers, and more.

These are not new strategies for Schultz, and that experience is likely why he was brought back to the company. His tactics have consistently ridden the balance of dissuading organizing through material improvements to worker conditions as well as direct language and actions against the unionizing narrative.

“If Starbucks goes to the extent of doing an audit and figuring out, ‘What are the major needs of the employees and how do we keep up with that? How do we anticipate this? How do we solve that?’ Then Starbucks would be on the right path, because in the past they have tried and done that and they have been ahead of the game by giving benefits, as I said, for…even part-time employees,” Shankar said. “That’s the way to try and resolve these issues in my view.”

Those familiar with Schultz’s early days as Starbucks’ leader know he’s been at the forefront of making Starbucks a union-free company with strategies like these. One of his often-cited quotes on the subject comes from his 1997 memoir Pour Your Heart Into It: How Starbucks Built A Company One Cup At A Time, reflecting on how the company shed its initial union while he served as CEO.

“I was convinced that under my leadership, employees would come to realize that I would listen to their concerns. If they had faith in me and my motives, they wouldn’t need a union,” Schultz wrote.

After its purchase of and merge with Peet’s Coffee and Tea created some internal tensions around finances and the two company’s cultures, Starbucks was hit with a unionizing run. By 1985, several Seattle-based workers had successfully formed a union under United Food and Commercial Workers. As Schultz recounts, the early days of his CEO run were mired with low morale, distrust and discontent from now-merged Starbucks and Peet’s employees. They saw Schultz as an outside force looking to sacrifice a rich homegrown company history in order to modernize and scale the business; his tactics to win their trust, which we see playing out again today, included making his case in-person at the company’s roasting plant.

“My goal, I announced, was to build a national company whose values and guiding principles we all could be proud of. I discussed my vision of the growth of the company and promised to bring it about in a way that would add value to Starbucks, not diminish it. I explained how I wanted to include people in the decision-making process, to be open and honest with them,” Schultz wrote.

Throughout 1987, the year Schultz joined as CEO, the union movement began to lose steam. Baristas themselves took on the mantle of decertifying the union, headed by an employee who had initially voted ‘No’ on the union campaign. Schultz recalls the main employee, Daryl Moore, being motivated to lead the decertification charge because of Schultz’s actions, leadership vision and promises kept.

“When he saw the changes I was making, he began philosophical debates with his colleagues and with the union representative, whom he knew. He did some research on his own and began an effort to decertify the union,” Schultz wrote.

By 1992, the company was once again completely union-free. Schultz had effectively convinced Starbucks employees that if management listened and acted with speed and efficiency to their concerns, an organized bloc of workers would be unneeded. One of the few strategic specifics that Schultz explores in detail in his memoir is how the company took operational and hiring feedback from workers. Martin Shaughnessy, a Starbucks employee in warehouse receiving, approached Schultz with the request for a department manager to organize the company’s distribution. Six months later, the company hired a new manager on Shaughnessy’s suggestion; Schultz frames this type of proactive response from company management as the actions that led to a decertified union.

“One day in early 1992, Martin came into the human resources department, bearing a letter, signed by an overwhelming majority of the warehouse and roasting plant employees, indicating they no longer wished to be represented by the union. ‘You included us in the running of this business,’ he said. ‘Whenever we complained, you fixed the problem. You trusted us, and now we trust you,'” he wrote.

“When so many of our people supported decertification, it was a sign to me that they were beginning to believe I would do what I had promised. Their distrust was beginning to dissipate and their morale was rising.”

Decertifying the UFCW union was indeed worker-backed, but it doesn’t paint the full picture to say it was solely a grassroots-supported movement, or that Schultz’s visionary leadership of a new company-partner dynamic was the only motivator. Union organizers from UFCW Local 1001 remember the saga having a more antagonistic approach from Starbucks and Schultz.

One of the roasting plant workers from that era, Anne Bellov, spoke with Politico about the months after Schultz’s CEO appointment and how the company set its stance toward the union. Though Schultz promised workers he would “honor that contract” from UFCW that he inherited as the company’s new leader, that promise didn’t last long; Schultz hit the reset button and began new negotiations between management and the union. During this time, Bellov remembers management embarking on the “normal stuff,” putting “pressure on those of us who were involved in the negotiations.”

Schultz attempted to dilute union sentiment during the second round of contract negotiations by involving not just roasting plant employees, but workers at all of the region’s stores. According to Bellov, the idea was that if Schultz had a larger audience to communicate his union-free vision to, then the vote had a likelier chance of failing. It had the opposite effect; workers at all the stores continued to support the union and the contract’s demands. It was then that Schultz threatened to renege on Starbucks’ agreed-upon contract terms to make union appeal less sticky.

An old UFCW leaflet summarized the union’s stance on Starbucks’ new contract concessions, including their dissatisfaction with allowing “long term employees to be terminated without just cause, reductions in medical benefits…reductions in work hours,” and letting the company “change working conditions at anytime — without bargaining!”

Starbucks’ new contract demands never had the chance to hit the negotiating table after the union decertification campaign materialized. Dave Schmitz, the lead organizing director for UFCW Local 1001 during that time, spoke with several outlets about his experience working with Schultz. His memory of events place the core of decertification energy further away from workers, claiming Schultz told workers that they’d “do better” if they left the union behind. He also claimed employees weren’t the ones who took the first step in legally dissolving the union.

“Starbucks actually filed the decertification petition. In my 30 years on staff at the union, it was the only management petition we ever saw to decertify a union,” Schmitz told Politico.

Regardless of whether his first major union bust was because of progressive leadership or targeted anti-union threats, Schultz has been doing something right in the eyes of Starbucks and the Board or he wouldn’t be back for a third stint. His steadfast vision and his tough tactics have kept the company union-free, and have even reigned in the movement from widespread support once before.

He’s also been effective in staving off union hunger with robust benefits compared to others in the food service industry. As of today, the company offers a “competitive” 401(k) plan, its Bean Stock equity reward program, paid vacation days and sick days for all employees, paid parental leave and public transit passes, among other in-store perks. The two benefits that have called the biggest attention over the years have been…

- the company’s College Achievement Plan, a partnership with ASU to offer 100% tuition coverage for over 100 fully-online bachelor’s degrees. This was the first program of its kind when introduced in 2014

- offering full medical coverage for eligible part-time employees since 1988, the first private company to do so as part of its internal benefits

What isn’t widely reported though is that the cornerstone of Starbucks’ progressive brand and benefits, its comprehensive health insurance for part-time employees, was actually enshrined by UFCW decades earlier, according to Politico reporting. At Starbucks, part-time medical coverage along with paid time off was already part of the approved union contract that UFCW negotiated and won when Schultz stepped in as CEO in 1987. Schmitz explained to Politico how unionized grocery workers in the Seattle region at the time were eligible for health benefits while logging 15 work hours a week; compare that to the average 20 hours a week part-timers have to work today to qualify at Starbucks.

Schultz, according to Schmitz, walked back on the benefits in 1987 after they were union-promised, using the narrative that the company would be able to better provide for its workers without a union in the way. It wasn’t until after the retail-side union disbanded (the roasting plant remained unionized until 1992) and effectively terminated part-time medical coverage guarantees that Schultz re-announced the benefits and claimed the nationwide standard as a Starbucks crowned jewel.

The narrative of Starbucks setting this precedent persists; Schultz himself brought it up in an interview with CNN in 2019. When questioned about his commitment to accessible healthcare after calling Medicare for All “unaffordable,” Schultz reminded Poppy Harlow that Starbucks was the “first company in America to provide comprehensive health insurance to part-time people.”

“I know a lot about this issue. It’s deeply in my heart,” Schultz said.

It is true that Starbucks was the first union-less private company to enact this policy within its internal benefits package, but the reality is that UFCW introduced these benefits to Starbucks workers first and rarely gets the credit. It’s fair to ask: Without the foundation set by unions and workers getting a taste of these union-provided benefits, would Schultz have still pushed to set part-time medical benefits as a company standard?

Schultz has his tool belt of strategies fully-stocked: drilling home a progressive narrative for the company’s history, fielding employee concerns in-person, arguing against the benefits of a union to employees and the media alike, destabilizing the organizing process through store-level management and other traditional means, and providing attractive benefits (for their altruistic merits, but also to have workers lose faith in the unionizing process).

“Studies have shown that for proactive management that actually anticipates employees issues ahead of time…actually makes the job of unions redundant. So that’s the key, the way to view it is that, ‘How can I make unions’ job redundant,'” Shankar said.

Once again, the company faces low morale, distrust and discontent from employees. Hobson admitted to the company’s failure in keeping up with their concerns, and the company says it’s now listening more intently since Schultz’s return. What did they hear from employees?

Starbucks Workers Have a Lot of Demands for Schultz

Since the start of the pandemic, Starbucks employees have focused their demands around a few key areas: better staffing, expanded benefits, and adapting the on-the-job environment to post-COVID realities.

“The demands of the union are not so much in the wages, but…the working conditions and the benefits that you have,” Shankar said.

There isn’t one set of unified demands across all organizing Starbucks locations. While each store is setting the terms of its own union battle, Starbucks Workers United has opted against rallying all stores behind a singular campaign. It does, though, give a high-level summary of the wins workers are putting in their sights: “organization policies, rights on the job, health and safety conditions, protections from unfair firings or unfair discipline, seniority rights, leaves of absence rights, benefits.”

Starbucks employees are of course still organizing for better wages as well (some hoping to secure minimum wages as high as $25 an hour), but Shankar is correct to point out the unique breadth of workers’ grievances, which reflect issues with specific Starbucks policies as well as a more generalized expansion of traditional union demands since COVID. Some of the specific concerns and demands of workers include…

- improving baseline pay to prevent things like workers “living paycheck to paycheck” or making “$24,000 as a full-time Starbucks barista last year”

- adapting all aspects of training and staffing to align with a more mobile order and drive-thru-based ecosystem, where there’s less interaction with customers and more opportunities for order errors

- better mental health care coverage to deal with increased customer agitation, offering support beyond the company’s provided Lyra app which has telehealth services but recommends employees find more complete (and expensive) support for sensitive issues like eating disorders

- “seniority pay…credit card tips…a voice in some of the decisions”

- proper shift scheduling to prevent “breakdowns over things like being behind on bills or even things like being understaffed on the floor. Like really, really poorly understaffed”

- finding ways to reduce turnover, especially for stores which “cannot keep employees or hire enough workers to continue under the strains of working in these conditions”

- longer and more in-depth training for new and legacy employees

- improvements to how the company’s in-store operations adapt to short-term fluctuations in demand, like wacky TikTok-inspired order modifications

More recently, in an attempt to course-correct the company’s lack of listening and to further give employees a chance to air out their grievances, Starbucks hosted several collaboration sessions between employees, management and Schultz. During these meetings, employees expanded on their concerns even further, listing out goals they’d like to see materialize like…

- “guaranteed hours,” “help with finding affordable housing,” “more paid time for community,” and “financial class”

- “higher tier experience,” “more labor,” “better quality check for supplies,” and “agree that customers are not always right”

Knowing Starbucks’ chief goal in this moment is to put a stop to union sentiment, the company heard these calls and responded with tactics, both before Schultz rejoined the company and since, that are part and parcel with Schultz’s strategic playbook.

Carrots and Sticks: Schultz is Reopening His Usual Union Avoidance Playbook

As I’ll detail below, though Starbucks is playing a balanced Good Cop Bad Cop with its unionization response, unionizing has not slowed at the company and the public square narrative is not very sympathetic to Schultz. As of now, it appears Schultz’s strategies aren’t working to stave off Starbucks Workers United. Let’s break down the carrots and the sticks in detail.

The first order of business for Schultz as third-time CEO was to terminate the company’s stock buyback program. Pre-pandemic, the company spent a whopping $10 billion on buybacks in a single year, pausing the practice in 2020. Before Schultz terminated the repurchasing program, Starbucks had already spent $3.5 billion in Q1. Spending exorbitant amounts of money to support stock owners is a public image issue as workers demand improved protections and pay, so even just on that front it makes sense that Schultz would take a shot at the company’s more affluent stakeholders to signal support for day-to-day employees. He framed the move as one that would “allow us to invest more profit into our people and our stores — the only way to create long-term value for all stakeholders.”

The listening sessions have also yielded interesting results; they’ve been some of the most constructive and, indeed, collaborative of Starbucks’ post-union strategies for engaging with workers. Going store-to-store and hosting open forums, Schultz made these sessions a priority upon his return and one of the first immediate changes to the company, with a goal of fostering solutions for “mutual thriving in a multi-stakeholder era.”

After consulting with thousands of employees, the company developed and delivered a new ‘carrot’ strategy for employees: Schultz announced a package of new benefits on the company’s Q2 earnings call that reflect many of the grievances and demands workers have been calling for for years. Starbucks Workers United called these material gains a win for the movement and for all Starbucks workers.

The new benefits include…

- an expansion to previously proposed pay increases. Starting August 1, all US partners will be hired at a minimum $15 an hour, pushing the average hourly pay to “nearly $17 an hour nationally.” On top of that, recent hires up until May 2 will either be bumped up to $15 an hour or get a 3% raise, “whichever is higher”

- more robust seniority pay, giving partners who’ve been with the company for 2-5 years a “5% increase or move to 5% above the market start rate, whichever is higher” while partners with more than 5 years of service will get “at least a 7% increase or move to 10% above the market start rate, whichever is higher”

- increased training opportunities across the board, but specifically a doubling of training time for both new baristas and new shift supervisors starting later this summer

- investing in credit card/debit card tipping infrastructure by the end of the year

- bringing back the coveted “Black Apron” program, which gives partners with a higher degree of coffee knowledge and skills a visual recognition to both other partners and guests

Congratulations to all the hard work of partners organizing at Starbucks–our campaign has pressured @HowardSchultz & Starbucks to announce many of the benefits that we’ve been pushing for since day one and we’ve proposed at the bargaining table in Buffalo. pic.twitter.com/w1aEcCzk6I

— SBWorkersUnited (@SBWorkersUnited) May 3, 2022

Compared to some of the company’s other recent tactics to dissuade union organizing, which I’ll expand on shortly, these benefits are a major improvement not only materially but image-wise for Starbucks. It lifts Starbucks’ floor wages to above the most recent national average for food preparation workers, which was $13.85 an hour in May 2021. The labor experts I spoke to, a few of who were sourced before this announcement from Schultz, advised for a similar change in strategic tune from Starbucks.

“Starbucks is a very profitable company that probably has the resources to pay their employees a little better, to increase and improve the benefits they have, to really pivot to being the sort of model employer that I think would be consistent with the progressive and liberal brand and an image that they’ve tried to cultivate over the years,” Clark said.

Before this benefits package, Starbucks had already announced an intended increase in pay in October 2021. The company promised to raise the wage floor to $15 by summer 2022 as well as offer 5-10% raises for tenured employees, meaning the actual new pay increases in Schultz’s most recent update come in the form of further new hire and seniority raises rather than a further increase to base pay. The initial announcement of a Starbucks $15 minimum wage also came just as the union movement started gaining steam in Buffalo.

If Starbucks is still trying to plant its flag as being ahead of the curve on employee benefits across the entire American economy, it’s struggling to maintain that narrative with these benefits; at least when it comes to wages, various other metrics put it no longer at the front of the entire retail and hospitality pack. In August 2021, the Washington Post found both restaurant and grocery workers had already crossed the $15 an hour average. The average hourly earnings for the whole leisure and hospitality industry landed at $17.56 in April 2022, while the retail trades as a whole averaged out at $19.46. The last year also saw major retailers like (unionized) Costco raise minimum wages to $17 an hour and Target boost its starting wage range to as high as $24 an hour.

As Starbucks Workers United said, these benefits are worth a “congratulations” for workers and are indeed an improvement over where things stood pre-union push. We shouldn’t forget though that even the more benign and materially-improving tactics from Starbucks are still an attempt to disincentivize joining the union. The harsher side of that fight, the ‘stick,’ has shown its face as well during this saga.

We can see this strategy in action with the very same set of new benefits, which when announced came with a major caveat: the new benefits packages would apply to everyone except unionized employees.

“We do not have the same freedom to make these improvements at locations that have a union or where union organizing is underway. Partners at those stores will receive the wages increases that we announced in October 2021, but federal law prohibits us from promising new wages and benefits at stores involved in union organizing and by law we cannot implement unilateral changes at stores that have a union,” Schultz said during the company’s Q2 2022 earnings call.

Starbucks isn’t wrong in acknowledging that the presence of a union creates an extra step for introducing new benefits: negotiating a contract. During pre-determined periods agreed upon by the company and the union, both parties would sit down to rehash demands, negotiate pay and working conditions, and certify a contract (or go on strike if negotiations go south). There is no law that says companies are unable to offer unions comparable benefits, though, and with a simple proposal of said benefits to each unionized store, both parties would be able to come to a midterm agreement on enacting changes outside of the traditional negotiation periods.

“He can’t give them those wages and benefits…unilaterally, but he can do it by proposing it to the union, it’s very simple to do. He’s being disingenuous there,” Clark said.

Tactics like these from Schultz are commonplace during union drives. A company will respond to union demands by introducing improved benefits in an effort to argue that workers don’t need a union to make material gains. Schultz basically said as much.

“The union contract will not even come close to what Starbucks offers you,” Schultz said in the Q2 earnings call.

The way this is being framed by Schultz and Starbucks is one step short of saying unionized employees will only get these new benefits if they reject the union and cease organizing. Coming right out and saying that would be illegal, though, under NLRA law.

However, legal experts like Matthew Bodie, law professor at Saint Louis University and a source for the New York Times’ story on the new benefits, say it’s “hard to see how this is that much different in practice.” If Starbucks continues to hint at these benefits being unavailable to unionized stores, it could violate labor law and Starbucks’ legal obligation to negotiate in good faith with the union if the NLRB determines the benefits proposal was done with animus against the union.

If Starbucks Workers United proved to be dismissive or combative to midterm improvements offered by the company, then Starbucks would have more of a leg to stand on in claiming the union was an obstructive force. There’s even precedent already set around this topic; when union-represented employees at Merck argued that the company’s withholding of new holiday ‘Appreciation Day’ for non-unionized employees constituted an unlawful act, the NLRB ruled in favor of Merck, citing the union’s previous unwillingness to explore “simple” midterm adjustments to labor contracts regarding changes to payroll administration and 401(k)s.

Regardless, dying on this hill will be a tough one for Starbucks with the NLRB’s watchful eye already looming over the company.

“The problem for [Schultz] is that he’s been engaged in an aggressive anti-union campaign since the beginning, and it’s going to be hard for Starbucks, I would argue, to make the case that they’re not doing this to chill the union organizing efforts,” Clark said. “If it looks like he’s withholding these from the unionized workers to punish them for union organizing, that’s an unfair labor practice, that’s illegal.”

Unions aren’t often negotiating for worse benefits, pay and working conditions than what a company is willing to offer. In fact, it’s usually the opposite; unions have heftier demands than what a company will compromise on, leading to militant labor action like strikes.

“I’ve been teaching labor and employment relations for I guess now 25 years. I’ve studied it, I have analyzed it, commented on it and worked with a lot of labor and employment relations professionals, and I am bereft of examples of where workers join unions and then end up, in bargaining, reducing the level of their benefits or worsening their economic conditions,” Bruno said.

If Starbucks Workers United ended up not getting these improved benefits, it’d likely be because Starbucks didn’t like their terms. It’s a negotiation after all, which takes two parties. Which party would be the obstructive force in keeping these benefits from unionized employees if the union is a fan of the “modest improvements” and is fighting to have them recognized?

Starbucks is saying that they can’t give union stores the new benefits they just announced. This is simply false. Our bargaining committees will demand these modest improvements be given immediately to all workers. Union-busting will not work— Starbucks will be a union company!

— SBWorkersUnited (@SBWorkersUnited) May 4, 2022

This approach from Starbucks, of claiming the union is keeping benefits from workers, is seen as outdated by the experts I spoke to.

“The typical playbook is, you try to reach out to employees and then point out that you lose benefits if you join the union and so on, but I would advocate a different approach. That’s kind of perceived as threats and very defensive,” Shankar said.

“I would advocate a more proactive approach, as you call it progressive approach, which is going on saying, ‘I want to use this as an opportunity to set up listening sessions with my employees, not only in the locations that want unionize, everywhere. So I basically do a deep dive into their issues and problems right away, and then anticipate that,'” Shankar said.

Other more aggressive tactics against this labor wave started under Kevin Johnson, but labor experts suspect Schultz was involved in the strategic process even from the outside, considering he made a public appearance on the subject as organizing began in 2021.

“Clearly the leadership at Starbucks, the CEO Kevin Johnson, made the decision about how they would respond to the union, and I would guess that this was done in consultation with Howard Schultz,” Clark said. “My sense is that Howard Schultz was very much on board with the approach that Starbucks management took in opposition to the union, because at one point he actually came to Buffalo, New York which was the site of the stores that were the first to try to organize a union.”

When Schultz first reentered the labor battleground in the lead up to Buffalo’s consequential vote, his language against the concept of a union took a disappointed tone.

“No partner has ever needed to have a representative seek to obtain things we all have as partners at Starbucks. And I am saddened and concerned to hear anyone thinks that is needed now,” he wrote in a letter to partners on the day of his visit.

Starbucks’ official messaging to partners as the vote approached was even more adamant about ending the possibility of a union. “We want you to vote no,” an email to unionizing Buffalo stores read. “Unless you are positive you want to pay a Union to represent you to us, you must vote no.”

Schultz has adopted more of the latter’s tone in recent months, painting a picture of the union movement that frames it with saboteur intentions and deceptive practices. The claim from Starbucks, officially filed against organizers to the NLRB, is that Starbucks Workers United has been intentionally keeping baristas from voting, as well as harassing customers and employees who were “unlawfully restrained and coerced.”

“I wasn’t there, but there are stories that people potentially had been bullied not to vote,” Schultz said in a leaked video meeting with Starbucks store managers.

Starbucks is sticking to this story and framing, both behind closed doors to managers and in public forums to partners. In his speeches, Schultz calls on all workers and managers to take up the battle cry against the union, for the sake of Starbucks, and to “collectively and individually…protect, preserve and enhance the company.” Here are some more examples of how Schultz has spoken about the union:

- Schultz references SWU as “an adversary that’s threatening the very essence of what you believe to be true”

- Reportedly, Schultz called this a “disruptive era” for Starbucks as it fends off unions that are “aggressively sowing division”

- “We can’t ignore what is happening in the country as it relates to companies throughout the country being assaulted, in many ways, by the threat of unionization.”

- When speaking to managers on their role during the union movement, he affirmed them by saying: “My faith and confidence in the future of Starbucks is based on my faith and confidence in you, not some outside force that’s going to dictate who we are and what we do.”

- Reportedly telling a barista and one of the lead organizers at a California store: “If you hate Starbucks so much, why don’t you go somewhere else?”

Adversary. Sowing division. Assault. Threat. Outside force. Schultz’s words speak for themselves, reflecting Starbucks’ view of the union and its strategies for keeping the company union-free.

Both before and during Schultz’s third stint, Starbucks has been accused of several traditional union-busting tactics, including…

- mandatory listening sessions, often referred to as “captive audience meetings” in the world of labor organizing, where management makes its case against the union

- upper-management visits to local stores to “monitor workers,” speak to workers one-on-one during break time, and give a helping hand with coffee orders and trash runs

- the alleged firing of several workers from Memphis to Ann Arbor who claim being targeted for their involvement in organizing, but which Starbucks claims was for violating company policies

- an acceleration of cutting hours and threats to freeze pay in unionizing stores

Many of these are claims and allegations, to be clear, but they’re front of mind for organizing workers and the general public. There are a number of layers motivating Starbucks to go to these lengths, but lately there’s been a unique extra layer with Schultz, one that was decidedly absent while Johnson was CEO.

“He’s taken this very personally, he built this company and he’s not used to people challenging his decisions…that doesn’t come off well to employees who I think really sincerely believe that what they’re doing isn’t detrimental to the company,” Clark said.

And indeed, Schultz admits in one of the leaked video meetings to having an individual stake in the fight: “I want to ask you to understand what it means to take it personally.”

Improved pay, improved benefits, and improved working conditions, which Starbucks workers have received since the return of Howard Schultz, are all positive. But they’re not the strategies shaping the national conversation; Starbucks’ other words and tactics are overshadowing any of the more worker-focused moves by the company.

“Schultz continues, I think, to ignore [collective bargaining] and treat his workers is if they really can’t make up their minds and they don’t know what’s best for themselves. And so I don’t see how either the carrot or the stick is going to work,” Bruno said.

Schultz’s Union-Busting Isn’t Working Like it Used To

Now we get to the global response. How are people taking Schultz’s actions? From analysis of various news reports and financial metrics, as well as the perspectives of the experts I spoke to, it appears Schultz’s union avoidance tactics are not being well-received.

Starbucks has likely spent millions of dollars already, including in exorbitant legal fees to successful union avoidance law firm Littler Mendelson, on its campaign to end the company’s union threat. Littler is known for defending and promoting tactics from the usual union-busting playbook, including opposing legislation that would “prohibit employers from requiring employees to attend meetings regarding the employer’s views on unionization,” otherwise known as captive audience meetings. Labor experts have seen these tactics time and time again, from Nissan to McDonald’s; Littler consultants and attorneys will join the fray and guide corporations to enact familiar tried-and-true strategies.

This time around, though, things are playing out differently for Littler, Schultz and Starbucks.

“At different historical periods that tactic can be effective. The problem here is that workers have lots of choices and they have maybe better choices. And these are relatively well-educated workers who know the law, who don’t feel as if they’re captured by this employer, and so threatening them with possible job loss probably isn’t going to have the same impact it might’ve had on some low wage factory workers a couple of decades ago,” Bruno said.

Though Schultz’s salary is only costing the company $1, labor experts say his anti-union strategies are costing the company much more than that.

“He seems to be making just one misstep after another. Somebody described him as the gift that keeps giving in terms of the union organizing effort,” Clark said.

Public sentiment against Starbucks and its tactics are only growing. Take a peek at r/starbucks on Reddit, an online community of over 218,000 Starbucks fans and baristas, and you find not only a pinned how-to guide on unionizing Starbucks stores but popular posts like this one:

Headline after headline back-linked throughout this piece shine a consistent light on various anti-union sentiments from Schultz and the company, which are shaping the public narrative; now there’s a legal battle for the company on the horizon, too.

Though Rossann Williams claims “there was no union-busting going on” at the initial Buffalo store, the NLRB disagrees and is validating, on a federal regulatory level, many of Starbucks Workers United’s and organizing employees’ grievances with Starbucks’ labor response.

After fielding dozens of unfair labor practice charges from organizers, the National Labor Relations Board issued a complaint against Starbucks that includes over 200 violations of the NLRA during the Buffalo campaign.

“It just makes the story: ‘Starbucks violating its own workers’ rights.’ And I don’t know how Starbucks and its brand benefit from that,” Clark said.

Though many of those decisions were made without Schultz as CEO, the NLRB complaint makes note of the “unprecedented and repeated” visits from Starbucks management, including Howard Schultz, as examples of the company’s union busting in action.

“They haven’t been convicted of 200 unfair labor practices, but the board has said, ‘we have probable cause that these are violations of the law, we’re charging Starbucks with these violations….’ We have to be careful to be clear that Starbucks hasn’t been found guilty of these at this point, but the board doesn’t willy nilly just make these charges,” Clark said.

Starbucks unfair labor practice filings across the country also continue to increase, rising steadily since the December Buffalo vote and indicating Starbucks’ strategies are consistently rubbing workers the wrong way.

Schultz’s moves have done nothing to stop organizing momentum, either. Unionization trackers have the number of SWU wins and certifications at 62 as of May 12, and the number of new filings per month has stayed consistently above 60 since February. The most recent wins for SWU include a close call in Oklahoma and a unanimous vote in New York.

“These kinds of rates of success, although it’s one company and the numbers are still relatively modest, the win percentage is at a rate historically high for a company. We haven’t seen union win rates like this probably since the passage of the National Labor Relations Act in 1935,” Bruno said.

The public outcry from workers aligns with the win count, with many of the interviewed organizers in the last few months expressing bewilderment, anger, and a lack of trust in Schultz and Starbucks’ good will. It’s making it much harder for Starbucks to control the narrative and convince the court of public opinion that they’re not acting in bad faith. Here’s just some of what they’re saying—

- “Since Howard took over, there’s definitely a feeling that anti-union sentiment is less covert in my store.” – Virginia Conklin

- “It was very, very bad. He was getting very aggressive with me.” – Madison Hall

- “Starbucks is finally being held accountable for the union-busting rampage they went on.” – Danny Rojas

- “We can resist and thrive, even among a storm of disinformation and fear-mongering perpetrated against our best interests.” – Brennen Collins

- “We’re doing card signing on the floor, because that’s our public space. But management is making people really nervous to talk about it.” — Casey Moore

- “They’re rolling up expensive suits to wash dishes and do trash runs. It’s almost comical.” – Jaz Brisack

The political winds are also blowing in favor of Starbucks workers. Not only has a Biden-appointed NLRB proven helpful to the union cause and bargained for workplace conditions that are more sympathetic to workers, but the administration has gone out of its way to get behind union movements sweeping the country. Barely a week ago, Secretary of Labor Martin Walsh and Vice President Kamala Harris invited union leadership from both Amazon and Starbucks to the White House for a (albeit, relatively symbolic) round-table on recognizing organizing rights and sharing the successes of their work. Other leaders within the current administration, including progressive legislators Sen. Bernie Sanders and Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, have both cheered on the movement in person and on social media.

You’d think investments into tactics that preserve the profit ratio of the company would at least keep Wall Street bullish on the company’s convictions and future, but even they aren’t confident in the strategies Schultz and Co. are wielding. Investors and analysts are writing to clients expressing concern about Starbucks’ standing, the cost of its various legal fees and potential benefit increases depressing stock value, and the company’s losing narrative battle. They’re specifically calling attention to…

- “deterioration in brand perception if the union battle continues to make headline news”

- “addressable problems in the near term are probably much more expensive and time consuming to bear results”

- “wage hikes or growing momentum behind the unionization efforts…[making them] more bearish on the stock”

The company’s own investors warned leadership that this would be the outcome of an aggressive union avoidance mission. A group of shareholders, spearheaded by Trillium Asset Management, wrote two letters to Starbucks leadership pleading with them to “publicly commit to a global policy of neutrality” with Starbucks Workers United.

“Starbucks has worked hard to create a positive brand reputation rooted in pro-partner sentiment. We believe that Starbucks’ reputation may be jeopardized due to reporting of aggressive union-busting tactics,” the letter stated.

With Schultz as the company’s leader, the company’s stock value has consistently dropped, besides a recent peak after a Q2 earnings report showed another quarter of strong revenue numbers. However, it’d be a stretch to attribute that recent spike to Schultz’s leadership specifically considering he rejoined at the end of the quarterly period. Some more recent metrics show the percentage of portfolios holding Starbucks stock is up around 3%, indicating potential rebounding confidence in investor sentiment, though it’s yet to have an impact on the stock’s overall valuation.

The reaction from consumers is a little more mixed, and whether the union campaign will impact in-store sales in the short term is still in question, trending towards ‘no.’ A BTIG survey of nearly 1000 Starbucks customers found that 68% of consumers, an overwhelming majority, would be unaffected by a union campaign in their Starbucks shopping frequency. But the more esoteric battlefield of brand perception is still at risk, as Trillium and Co. pointed out. A different survey by Blue Rose Research with a larger sample size of 2515 customers found nearly 70% of Starbucks customers believe baristas “need a union” to secure “higher pay and benefits, worker safety and fair schedules.” So even if materially customers have yet to boycott alongside workers, the union movement is still winning the narrative battle.

All in all, through opposing the union movement Schultz and Starbucks have yielded the following: A union-supportive Starbucks community. Union win after union win across the country. The NLRB legally validating worker grievances. A slew of bad headlines. Concerned investors. Under-performing stock. If Schultz’s goal in returning to the top of the company was to effectively convince not only workers but the world that Starbucks was better off without a union, he’s failing to meet the mark.

What could put more power back in the hands of Starbucks to dictate the outcome of this situation is the current macro environment, which is being littered with layoffs. Robinhood, Carvana, Netflix, Amazon, Wells Fargo, and a number of other companies have announced labor cuts or hiring freezes in even just the last several days. If Starbucks lays off a number of workers due to difficulty managing operating expenses, which increased almost 18% in Q2 2022, or if workers fear that their unionizing wins will lead to mass layoffs, it could put a pause on union energy. However, mass layoffs could read as more aggressive union-busting by Starbucks, which as we’re seeing isn’t working in Schultz’s favor.

The strategy that has been received the best is Schultz’s new benefits package for workers, and labor experts agree that these kinds of proactive moves that assuage Starbucks partners’ concerns are the company’s best path forward.

“In the current environment where unionization is actually snowballing, it needs to be really having a more proactive approach…and see how best they can have a partnership win-win where they have to compete against other food or coffee chains,” Shankar said.

Will we see these expanded benefits, and the indication that they won’t be shared with unionizing employees, “chill” union sentiment as Starbucks Workers United claimed?

“In the retail sector from my own work I can say that some of these moves can sometimes have a bit of an effect,” said Peter Ikeler, Ph.D., Associate Professor of Sociology at SUNY College at Old Westbury.

“At Target, I observed that there was some element of welfarism, some pretty low rent benefits that were provided or offered at least to employees and at least in the context of a high turnover workforce that was highly precarious and highly transient, sort of by design in terms of who they were hiring and how they were hiring, that this can have some dissuasion effect or at least mitigate the appeal of some collective organized alternative, like a union,” Ikeler said.

Unfortunately, Starbucks’ asterisk on these benefits for organized baristas backfires on an altruistic message of “[reintroducing] joy and connection back into the partner experience.”

Another surprising layer is that, even before the first store unionized, Starbucks leadership was already doubtful of its ability to wield either the carrot or the stick effectively to keep labor costs down and employees satisfied.

“Our wages and benefits programs may be insufficient to attract and retain the best talent,” the company wrote in its quarterly SEC filing in November. “Our responses to any union organizing efforts could negatively impact how our brand is perceived and have adverse effects on our business, including on our financial results.”

Workers may also note that, though benefit improvements were asked for for years and were not listened to as Starbucks admits, they finally saw significant pay and workplace improvements only after a watershed unionizing movement put pressure on the company.

“In the aggregate, I would say it’s a good thing, right? It’s a good thing that the drive to unionize is in whatever way raising the bar for workers,” Ikeler said.

To our CEO audience: What would you have done differently? If Shankar were Howard Schultz, here’s what his main strategies would be instead:

- “use all the marketing and the PR channels, particularly social media channel, to project these proactive initiatives”

- “highlight all of Starbucks’s initiatives in the past to be ahead of the curve”

- “reach out to all those people in the unionized locations one-on-one and try to meet them and try to resolve very sincerely their problem”

- “go actively and manage the public policy officials, government officials perception, and be willing to state that we are front and center keeping our employees at the front and center of our initiatives and thoughts”

As CEO, Who is Schultz Responsible To?

We’ve gone over a lot of context on Schultz’s background in keeping Starbucks union-free, his recent methods and how the current SWU movement is playing out. Let’s distill all of this down into some more actionable analysis for companies and their leaders.

It’s an understatement to say Schultz had a difficult task ahead of him when he rejoined Starbucks. By the time his third CEO saga began, it could be argued there was little the company could do to both keep a union at bay and retain its coveted progressive brand. Regardless, it was his chief duty to take on this challenge and determine how the company would respond.

“Leadership style of the CEO can be a huge factor. A very vocal and visible CEO can set the tone all the way down to the shop floor,” said Todd Vachon, Ph.D., Assistant Professor of Professional Practice in Labor Studies and Employment Relations as well as Director of the Labor Education Action Research Network at Rutgers University.

Even if a CEO and their leadership team believes wholeheartedly, as Schultz does, that a union is the wrong option for a company, labor experts argue that both black letter law and the essence of modern leadership make it a CEO’s responsibility to support and engage honestly with employee grievances.

“His role as CEO is not principally to maintain pleasant employee-management relations, as welcomed and as encouraged as those are, but to respect the will of his employees to be collectively represented in all areas that impact the employment relationship,” Bruno said.

“The right to organize a union free from interference is enshrined in the National Labor Relations Act, and CEOs have a responsibility to let the process play out and let the workers make their decision free from coercion,” Vachon said.

When analyzing the standard power dynamics of corporate America today, it’s an agreed upon duty that a corporation’s goal is to maximize profits in the interests of various stakeholders, but mostly shareholders. Such is expected in the heart of Western capitalism. Some experts even argue it is a company’s legal responsibility to prioritize profits above all else. Get Wall Street analysts and shareholders on your bad side, and a company’s growth narrative can tank.

“CEOs are of course beholden to shareholders. Unfortunately, many managers see unions and the wage and benefit increases they typically entail as a hindrance to their competitiveness in the market,” Vachon said.

Looking at the CNBC article on Wall Street’s reaction to Starbucks’ strategies, shareholders have a number of concerns with how Schultz is handling the situation, including that they think Starbucks is spending too much money to stop the campaign. This includes spending too much on improved benefits, another layer of CEO motivators at odds with workers.

“Clearly the CEO has to take into account the interest of multiple stakeholders. One would hope that the main stakeholder of concern to the company would be the employees who in expressing the desire for a union are sending signals that they’re not happy with working conditions and the situation in their workplaces. But a CEO also has to be aware of the interests of managers in the stores, of executives of the company, and shareholders of the company,” Clark said.

In an age of ESG competitive edges, the tides of corporate responsibility are shifting away from just shareholders. It’s hard to say capital performance will ever stop being the chief concern of businesses in America, but CEOs are at least signaling that it’s their duty to expand the scope of responsibility.

In 2019, 181 CEOs signed an updated Statement on the Purpose of a Corporation, where they reframed a corporate responsibility of “shareholder primacy” for a “modern standard.” The various CEOs and the Business Roundtable identified these new chief goals as…

- “Delivering value to our customers”

- “Investing in our employees”

- “Dealing fairly and ethically with our suppliers”

- “Supporting the communities in which we work”

- “Generating long-term value for shareholders”

Scroll down to the statement’s signatures and you’ll see a familiar name standing behind these goals: “Kevin Johnson, President and Chief Executive Officer, Starbucks Corporation.” Actively opposing unionizing Starbucks workers who’ve called out issues with pay and the workplace, and potentially holding new benefits back from unionized stores, creates friction with the standards of “compensating [workers] fairly and providing important benefits” that CEOs, including ex-CEO Johnson and by association Starbucks, have set for themselves in the modern age.

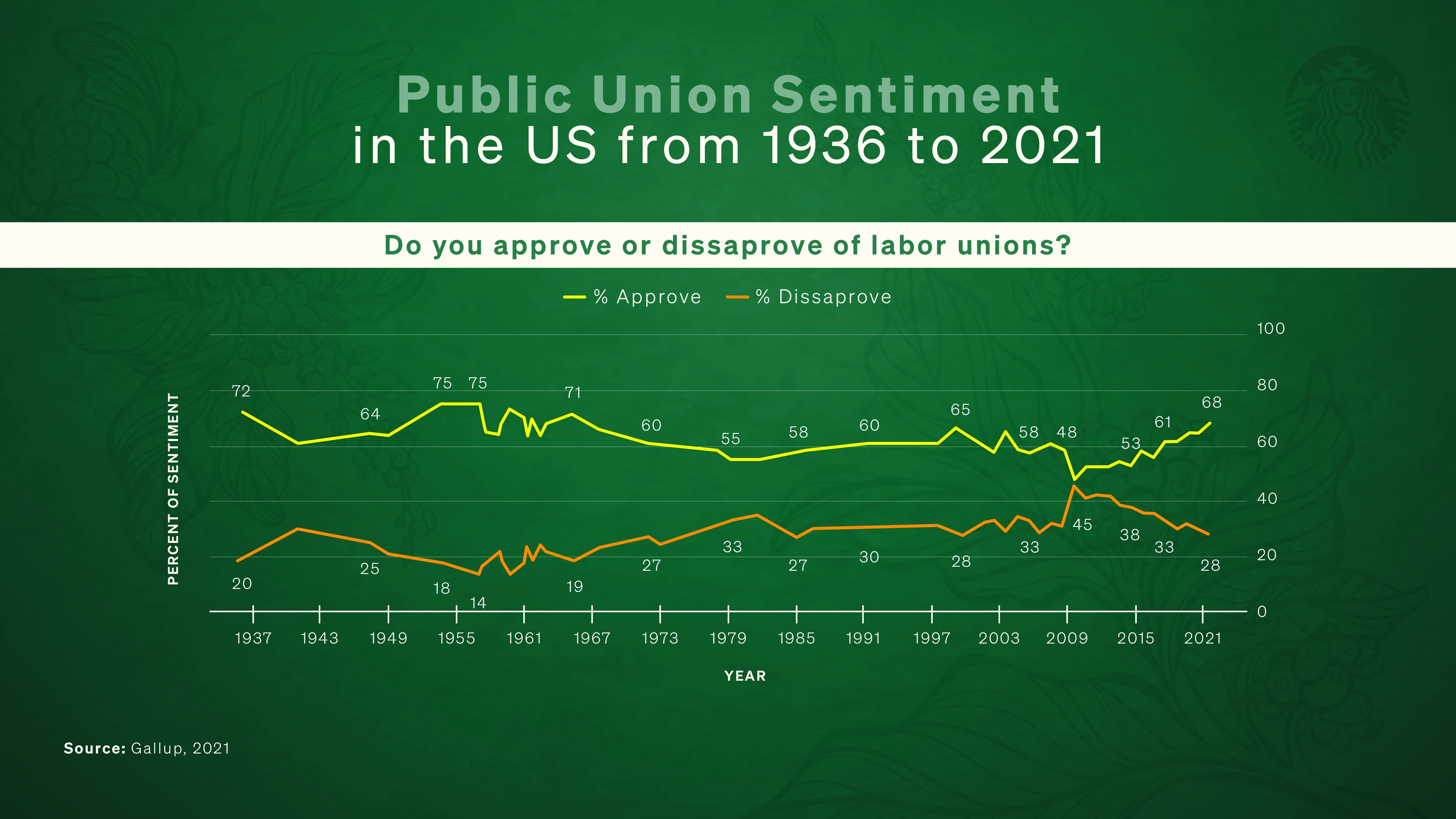

Schultz is also beholden to the company’s progressive brand, a major selling point for Starbucks and one of the main areas investors and analysts are calling out as at risk. Public sentiment towards unions today is at a widely-reported 57-year high, with 68% of US citizens holding favorable views of unions. If the company continues to antagonize the union, it could very well turn paying customers off to the brand; a Harris Poll sentiment study of almost 2000 American consumers backs this up as well, with 71% of respondents saying they want to see more service-industry companies unionized and 42% of respondents saying they’re less likely to shop with a brand that’s trying to stop a unionizing campaign.

“Starbucks is not the first, but it’s certainly the most visible self-styled progressive company that has experienced unionization efforts by dissatisfied employees. The fundamental differences between labor and management still exist, even in liberally-branded green, socially progressive companies,” Vachon said.

If anything, people are asking for a return to form from Schultz, embracing the values he and the company say they hold dear. Trillium’s letter to Starbucks leadership summarized well how many of the engaged parties, from workers to investors, see Schultz’s responsibilities in this moment:

“This group of investors encourages Starbucks to pivot to a more collaborative and mutual relationship with its unions to uphold its reputation and in keeping with the spirit of the ‘empty chair’ that founder Howard Schultz imagined for partners in leadership and board meetings.”

“If you would ask anybody two years ago, ‘what are the odds of Starbucks having 50 of their stores unionized and 250 others having organizing campaigns,’ you wouldn’t find anybody who knows anything about union management relations saying that’s a possibility in the least. So, you think someone’s going to look at this situation and say, ‘we’ve taken a few embers here and we’ve turned it into an inferno and unless we want to continue to burn the good will of employees across the country, we’ve got to do something different,’” Clark said.

Unions May Reduce a CEO’s Pay and Profits, But Not Necessarily Company Productivity

At the end of the day, all of this comes down to how unions are perceived by corporate America and management or else Starbucks wouldn’t be spending so much time and money to keep one at bay.

The heart of Starbucks’ and Schultz’s arguments are that a union presence within the company would obstruct progress, create friction between employees and management, and overall harm the company’s future.

“These intermediaries have demonstrated that…they [do] not operate in the best interest of partners,” Starbucks says on its union FAQ page. “We can move much more quickly than a union, engage with you directly when you need it most and be responsive to partner needs on an ongoing basis.”

How rooted in reality is this view? Should CEOs in today’s social and political environment fear unions?

There are studies that validate both sides of this argument, but it seems a significant amount of them say ‘no,’ that indeed unions are not the existential threat on corporate success that they’re made out to be. That doesn’t mean unions don’t have an operational impact on companies, though, and these impacts are important for CEOs to understand if they’re to thoughtfully engage with their own union movements.

One of the chief compendiums of research against unionizing comes from the conservative policy-making think tank, The Heritage Foundation, which on the subject of labor is a right-to-work-supporting organization that often argues in opposition to collective bargaining. In its report What Unions Do: How Labor Unions Affect Jobs and the Economy, the organization sifted through several academic studies and landed at the conclusion that unionized firms “shed jobs more frequently and expand less frequently than non-union firms” due to the analysis that when push comes to shove, unions fight to retain better benefits and pay rather than higher levels of employment. If at the negotiating table the two parties come to the conclusion that increased financial hardship must force a decrease in labor costs, unions will usually opt for protecting senior employees, laying off new hires and preserving high pay instead of lower wages for more workers.

This analysis is backed up by other studies like NBER’s more recent 2002 analysis of whose employment is actually impacted by unions; it found “more union involvement in wage setting significantly decreases the employment rate of young and older individuals relative to the prime-aged group,” in part due to unions needing to “balance out the gains from higher wages against the losses from resulting reductions in employment.”

The think tank also cites studies that show companies with recently formed unions reduce capital investment by 30%, and the author argues that even though unions do raise wages for workers across the board, they “do not increase workers’ wages by nearly as much as they claim.”

In refuting the idea that unions guarantee higher wages, the report’s author James Sherk says higher wages are already present at companies where union campaigns take hold.

“Unions do not organize random companies. They target large and profitable firms that tend to pay higher wages,” he said.

Large and profitable, perhaps yes. But the idea that unions go after firms that already pay high wages doesn’t align with high-profile examples like Amazon, Starbucks, or other food service unionizing campaigns where companies are often critiqued for their low pay. It wasn’t until recently that Starbucks brought its minimum starting wage to $15 an hour, and calling that a “high wage” is hard to argue considering that $15 doesn’t reach the true living wage minimum across the US, even in states ranked for their low cost of living.