Schools Struggle to Reach Their Education Technology Goals. Here’s Why and How To Fix It.

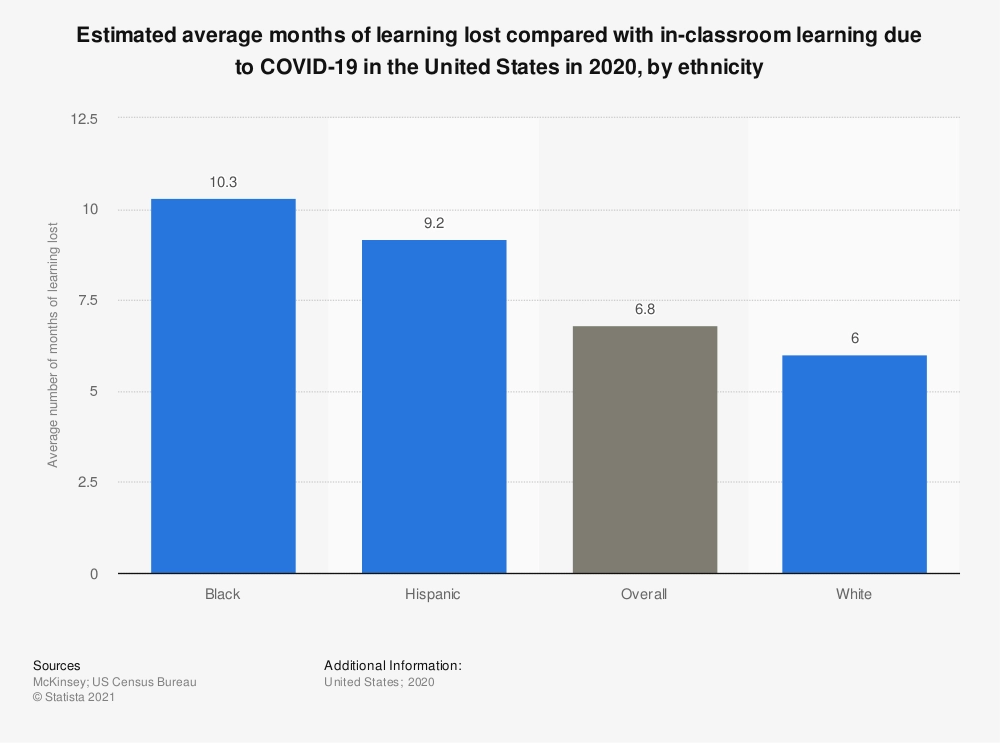

As we hit the two-year mark of the COVID-19 pandemic, the education sector continues to struggle in adjusting to virtual and hybrid education at scale. In 2020, McKinsey estimated that, due to COVID closures and the abrupt transition to online education, kids lost almost 7 months of learning regardless of socioeconomic background, a level of learning loss that educators expect could cause ripple effects for years.

The key strategy to combatting this disruption has, naturally, been to create flexible learning environments that rely on quality online learning solutions, gamification, 1:1 technology, and other education technology investments. What was for many schools a “band-aid fix” to a short-term problem, though, is still actively needed during the pandemic, and according to extensive research from the EdTech Evidence Exchange, still hasn’t become a confident part of the learning ecosystem.

The EdTech Genome Project’s final report from 2021 concluded that the effectiveness of edtech solutions in the classroom is sporadic and uneven across the country, even though spending on edtech is in the dozens of billions of dollars. Even before the pandemic, research by LearnPlatform found usage goals were resoundingly missed, with nearly 50% of schools reaching 50% or less of their goals.

In the context of the pandemic, education technology integrations can’t catch their breath for a second either, continuing to operate under a stressful adoption scenario. With the contagious omicron variant spreading, schools across the country are going back to temporary distanced learning to mitigate the virus, including in Oklahoma, Minnesota, Arkansas, Oregon, Utah, and more.

The United States Department of Education has been attempting to suture the wounds of COVID learning loss and continued hybridized learning disruption, with 46 different state plans for $122 billion in federal funding to help schools recover; much of the funding is going toward edtech programs. The money is there to support edtech adoption, but effective usage remains elusive, and the stressors of the moment only make adoption more difficult. If integrating education technology confidently is still a struggle for most schools, how can schools determine what applications to use, how to use them effectively, and how to make them accessible for all students?

We sourced five different edtech experts to weigh in on the challenges of a persisting edtech usage gap, and how to make the best use of available resources to make a more confident edtech investment.

Making EdTech Applicable for Each School’s Needs

“The way in which we can help the children is, in essence, to ensure that we are meeting them where they are.” – Neal Shenoy, CEO & Co-Founder, BEGiN

Educational gaps vary drastically based on location, community values, demographics, and various other factors, which contributes to the challenge of determining appropriate applications. Lindy Hockenbary, K-12 instructional technology consultant, author, and founder of InTECHgrated Professional Development, emphasizes the importance of schools selecting tools that use research to justify the ‘why’ behind their features and methods.

“I recommend every edtech company have a resource that…cites specific research that supports the features and functionality of the product, and explains why those features and functionalities are backed by those research-based instructional practices,” she said.

Dr. Dean Cantu, Associate Dean & Director of Education, Counseling, and Leadership at Bradley University, sees three goals school districts should implement to achieve their objectives. These include ensuring students have access to technology, personalizing the technology, and allowing the technology to create culture.

“The Computer Science Teachers Association is one of the advocates for this framework that allows them to basically maintain their academic integrity, their core principles, while still trying to integrate technology into the teaching and learning process,” Dr. Cantu said.

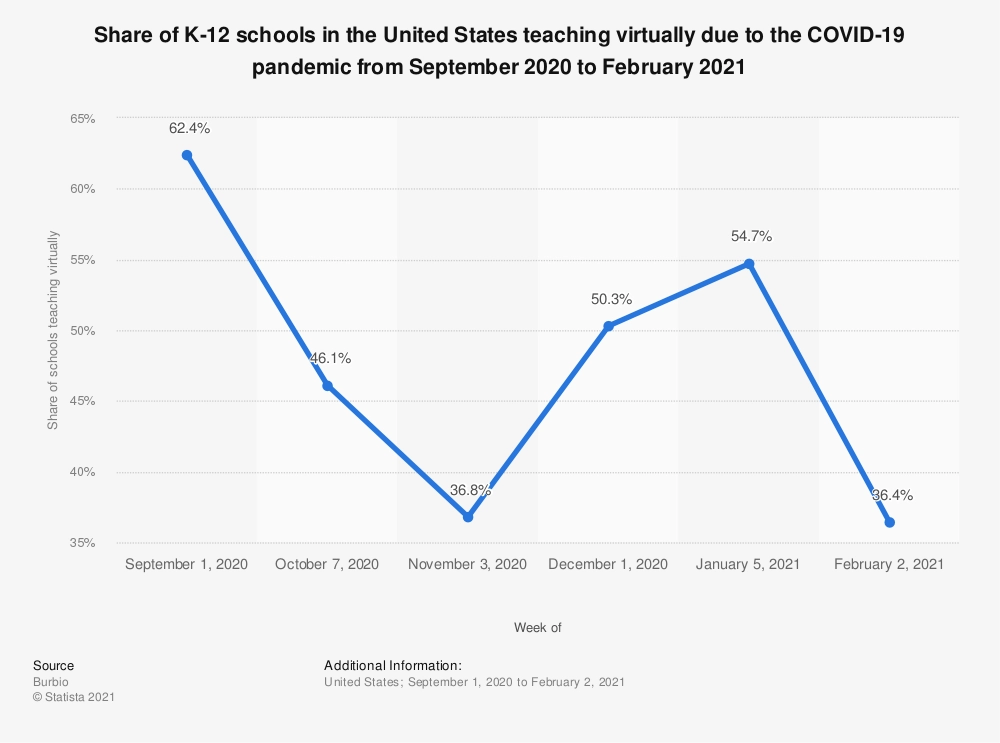

Allen Drennan, Lumicademy Principal, is a major proponent of Dr. Cantu’s first proposed goal—ensuring students can access the technology, especially in rural settings. Another component of edtech accessibility, says Drennan, involves acquiring appropriately-sized solutions and alleviating security and availability concerns by not solely relying on cloud service sharing. This is more important now than ever because of how many schools are still teaching virtually and transitioning back to online learning. According to Burbio, in late 2020, around 60 percent of schools in the United States were teaching virtually due to COVID-19. That number was still above 50 percent in early 2021.

“With a disparate array of education tools and products, each with their varying security models, using different cloud services and back-ends that may not meet organizational up-time requirements, and basic LTI integration incompatibilities between edtech products, IT organizations are shifting their focus into solving these kinds of problems,” Drennan said.

On the other hand, Amanda Kocon, CSO of Edmentum, emphasizes Dr. Cantu’s third goal, the importance of culture when selecting applications.

“We start by thinking really deeply about the local context, meeting with folks locally, understanding context, needs, challenges, what assets a school district or set of schools or community has to bring to the table as well because those are very important,” Kocon said.

This can be especially important when considering the type of learners, the students are, whether they learn best tangibly, digitally, or socioemotionally. Neal Shenoy, CEO & Co-Founder at BEGiN, supported this notion.

“We serve young children, and as an early learning solutions provider, we appreciate that children have very specific ages and stages of development that we have to be able to provide for,” Shenoy said.

Accessible EdTech is Useful EdTech

“What is necessary to one student is beneficial to another student.” – Lindy Hockenbary, Founder, InTECHgrated Professional Development

Even if schools pick the best technology for their needs and populations, it won’t be beneficial unless it is accessible to all students. Dr. Cantu acknowledged the pandemic has only highlighted this already existing issue.

“The digital divide existed long before the pandemic, but during the pandemic, we highlighted the impact of the digital divide on teaching and learning from many of our students,” Dr. Cantu said.

According to Kocon, education entities can close this gap by looking at potential edtech partners’ priorities to make sure they include accessibility. Other key aspects to examine include seeing if the technology is available both online and offline, especially critical for rural schools with spotty broadband.

Hockenbary shared two recommendations to ensure edtech is accessible to all students. She explained that districts should invest in Universal Design for Learning (UDL) training to create a proactive approach, as well as look for digital tools with accessibility functions built-in, such as picture dictionaries, translation features, and the ability to adjust the size, spacing, and font of the text.

“[UDL] takes a very proactive vs. reactive approach. So it doesn’t take the approach of, ‘oh, we’ll deal with this once we have a student that needs this accommodation,'” she said. “By choosing tools that already have these features built into them, schools are ensuring that every student has access to these features if needed.”

Leveraging the “Right Resources” Makes for Smarter EdTech Investment

“Many districts look at piloting at a small scale; doing it initially as a pilot, and using that to guide and inform their decision-making process.” – Dr. Dean Cantu, Associate Dean, Bradley University

Maybe a school district thinks they have narrowed the scope and identified what they need based on their community. What is the next step to ensure they make a financially sound decision and select the exact tool that will meet these needs? Kocon thinks schools need to pose meaningful questions to further narrow the scope.

“What are you trying to use technology to amplify? How is it going to be used in the classroom during the day? What’s your vision for instruction if it’s for instructional purposes? Then you actually begin to narrow the aperture a bit in terms of what’s available to you for that particular use case,” Kocon said.

Dr. Cantu supported this approach, adding that teachers should also be involved to gain insight into their classroom needs. Once the scope is narrowed a bit, Hockenbary suggested three resources, the first being a digital learning playbook that can plan, research, pilot, purchase, and review the effectiveness of a tool. The second source is an edtech pilot framework used once the resource has been selected and the school is piloting to determine its effectiveness with data. The final resource is a 25-page guide with recommendations and insights for schools making ed tech purchases.

The road to accessible edtech selections and implementation is a long one, but if done correctly, it may slowly begin to chip away at the damage the education sector has seen from the pandemic.